Mel Plant, BA Arabic and Turkish

For all the many hours of rolling news footage, thousands of articles, protests and debates, it’s hard to find someone who is sure they know, well, anything about Syria – and if you do manage to find a so-called expert, with all the keys to solving the puzzle of the country’s ongoing revolution and civil war, they end up being just as uninformed as any other commentator. A PhD student friend of mine, Duncan Wane, once wrote, ‘if anyone tells you that they understand Syria, don’t listen to them. Actually, no, that isn’t strong enough – hit them’. To sum up: we should be confused about Syria, and if you think you’re not – think again.

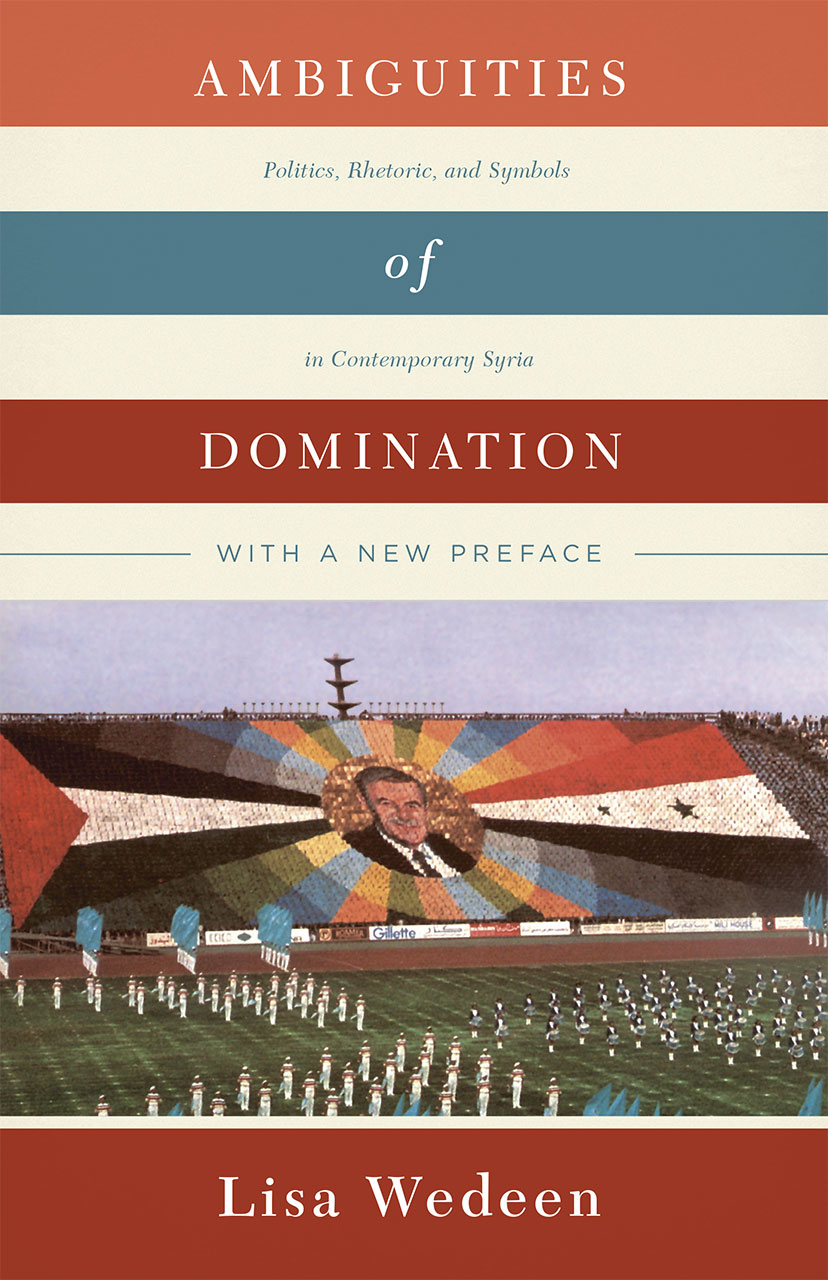

Most academic works on the Middle East tend to be verbose but fairly uninspiring, with little new commentary or analysis to offer. Perhaps this is because many authors choose to write on the Middle East as a whole, and on long stretches of its history as well. This minimises any knowledge disseminated in favour of the broad strokes of whatever the author’s favourite picture of the region is. Wedeen’s work is the proverbial diamond in the rough: concise (just 160 pages long, not including footnotes – should this be endnotes?), yet full of political theory and analysis which not only enlightens the reader as to the nature of Hafiz al-Assad’s Syria, but also contextualises the current crisis.

Wedeen is a professor in political theory and comparative politics. This background shows in the slightly heavier sections elaborating on theories of dictatorship in practise. Nonetheless, the book is perhaps the most-readable academic work I’ve ever come across. Through analyses of Syrian government and society political and cultural outputs, as well as methods of policing, Wedeen creates a concrete theory of the ‘ambiguities of domination’ to challenge prescriptive theories and cement the book’s status a go-to read on Syria.

The central theory proposes that in Syria, authoritarianism is – or, perhaps, was – reliant not upon the beliefs of the Syrian people, but their actions. Whereas many common theories hold that authoritarian leaders seek to change the hearts and minds of the people, Wedeen highlights a politics of ‘as if,’ where citizens will act as if they believe the lies and mythology of the regime, even going as far to create their own. Telling passages analyse regime rhetoric and how embedded and replicated it was by Syrians, despite a lack of belief. Wedeen also analyses counter-regime outputs and how even these worked within the rhetoric and mythology of the regime.

Ambiguities of Domination is an engrossing academic work, which manages to span its analysis from jokes told in the home to regime newspapers. Most telling is a passage relating to the nature of interrogation and military domination, which Wedeen relates back to 1984. Whereas in the novel, Winston, for a moment believes that ‘2 + 2 = 5’, the purpose of interrogation under Hafiz al-Assad was to make people proclaim that they believed such facts purported by the regime. To be forced to say you believe, even when you don’t – as to be forced to confess to a crime that you haven’t committed – is to be under the knowledge that you are ‘someone that will obey,’ which comes with a set of psychological and political reactions which allowed the regime to continue unhindered for so long.

This insight into Syrian public and political life under Hafiz al-Assad allows us to better understand the reasons behind the Syrian revolution and the shape of citizen transgressions against the Assad regime. Doubtless, there is still much more to unravel and ‘solve’ within this current crisis, but Wedeen’s work illuminates a sliver of the necessary pieces of the puzzle.

I absolutely recommend reading this briliant work to anyone who wants understand, well, anything about Syria.