By Lucy Nolan, BA Social Anthropology

“Vignettes of everyday life humanise refugees and remind the audience that they are ordinary people in extraordinary situations.”

This one-man show follows Hamzeh Al Hussien in a captivating retelling of the events of his life so far. As a disabled migrant fleeing Syria in search of safety, Hamzeh’s physical and emotional journey is one of hardship, dignity, strength, and self-acceptance. Penguin is a dynamic and inclusive experience, performed in English and Arabic with subtitles for both. The story flickers between three distinct times or locations; his native Syria, the Za’atari camp in Jordan, and Newcastle. Hamzeh’s passionate performance, along with the voice of his brother off-stage and audience participation, fully immerses the audience.

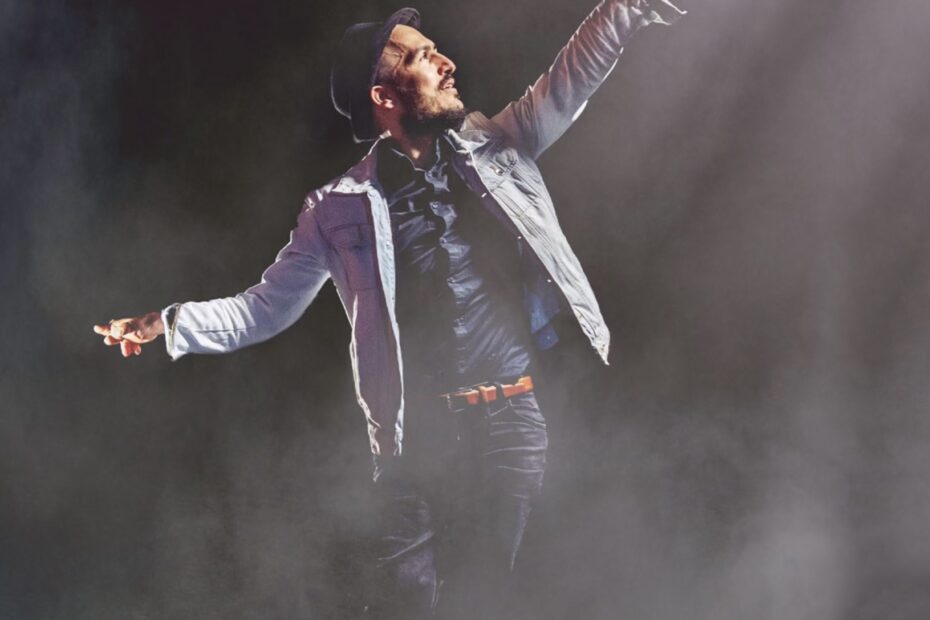

Penguin is almost entirely made up of anecdotes where difficult memories are interwoven with touching and funny ones, with Hamzeh often sharing moments which are ‘a good memory to think about’. Hamzeh’s frequent experience of prejudice and mistreatment meant he often avoided situations where he would be exposed to large numbers of people. The belittling nickname ‘Penguin’ stuck with him; we see Hamzeh grow to shrug off the face of ableism, and reclaim, as well as redefine, the name. His physical difference is no longer something he is ashamed of, with his presence shining across the whole stage; jumping and dancing on the tables in a hilarious reenactment of his first time in a club. Being the only person on the stage, with no distractions and nothing to hide behind amplifies these powerful moments; we are locked onto Hamzeh as he finally relishes being seen. Such moments, as well as vignettes of everyday life, humanise refugees and remind the audience that they are ordinary people in extraordinary situations, making scenes of bullying, ableism, and military violence even more shocking and upsetting. He laments, “We never thought it would be us” in a refugee camp. Hamzeh educates the audience on a Syria we have never known, one the media doesn’t show us – of life before the war, and life that continues despite the war.

Each story has ample time to unfold, allowing the audience to get to know and empathise with Hamzeh and his unique experience, something the British media does not do. At one point he tells us on average how many people live in one tent, how many tents in a row, how many rows in a section, and how many sections there are. We come to the figure of 84,000. The media often speaks of migrants using metaphors of natural disasters, such as a ‘flood’, ‘swarm’, or even ‘hurricane’, which anonymises and in turn, dehumanises these people. Each of them has a different history, dream, and passion. Hamzeh speaks of his friends and cousins he has lost, and his mother who is still in Za’atari camp. When does the migrant journey end? The struggle certainly doesn’t end on arrival, as racism, ignorance about refugees, and ableism persist, meaning the UK is not the safe haven many expect or hope for. However, as Hamzeh demonstrates, there is a place and purpose for everyone.

One such way to support this is by establishing and protecting safe spaces for creative exploration by overlooked communities, such as those who grew up in care, disabled people, and migrants. This is always important, but especially now as the leaders of our country continue to promote and pass anti-immigration bills, stoking ignorance and a sense of danger among the public. Whilst there are no more performances of Penguin in London, there are in other locations around England. Curious Monkey ‘are a theatre company of sanctuary’, who share the stories of underrepresented communities in their own creative expressions. Watch this space (and Penguin)!