By Roxanna Brealey History & Politics

The phrase ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’ is commonly used to express the subjectivity of attractiveness. However, since visiting the Wellcome Collection’s exhibition: ‘The Cult of Beauty’, my views on this have somewhat changed. The exhibition has helped me to deconstruct this phrase, as I have realised which global players have created narratives of beauty; and how the ‘beholder’s’ perspective is impacted by cosmetic industries and Eurocentric beliefs. Therefore, is beauty genuinely subjective on an individual level when the rules of the game are decided by larger, and more important contestants? The exhibition showcased different pieces and artefacts that could be broken down into three key themes: racialisation, corruption, and global obsession.

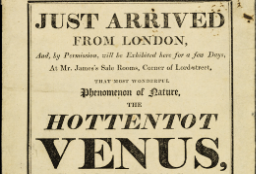

Racialised beauty is due to years and years of Eurocentrism. The key piece that explained the depths of Eurocentrism and the effects it had on beauty ideals, was a British pamphlet introducing a black woman who was called the ‘Hottentot Venus’; her real name was Saartjie Bartman. The pamphlet deemed her a ‘great natural Curiosity’, showcasing the embedded racism, inferiority, and exoticism of African features during the 1800s.

Unfortunately, this exoticism led to abuse by doctors and the public as she was exhibited around Britain and France. Her image was circulated across Europe, setting the precedent that sexual violence and racial fetishisation were acceptable. A more current and still ongoing example of how Eurocentrism has dictated beauty standards is skin-whitening cream (note the picture of the ‘Fair Lovely Glow Lovely’ cream). There is evidence from China to suggest creams and powders like these predate colonialism, but their worldwide circulation has been caused by colonialism. Creams such as the one pictured are estimated to be used by 40% of all African women; it all boils down to the concept that lighter skin is often associated with desirability.

Another key theme that I picked up on was that the cosmetic industry has pressured us into conforming to strict beauty standards, to the point that some of our autonomy over the way we look has been removed. A piece by Makeupbrutalism truly portrayed this for me. Within the centre of the mirror, it states that ‘I’ve mistaken social pressure with self-expression’ which perfectly links to the concept of choice feminism. Choice feminism is a contemporary ideology that emphasises every choice a woman makes as empowering. Whilst using makeup can be an empowering form of self-expression, there are boundaries that the cosmetic industry has crossed that make women feel the need to buy product upon product and erase their natural features.

In a sense, their agency over their self-expression has been replaced by the social pressure of the cosmetic industry. Plastic surgery (which in 2022 was estimated to be worth USD 41222.38) also needs to be acknowledged within the conversation. ‘The Disobedient Nose’ by Shirin Fathi is about ‘a nose that doesn’t want to be tamed’ which deals with Iranian women defying beauty standards and ignoring societal pressure to get rhinoplasties. Again, whilst plastic surgery is formally a choice, there are a variety of pressures involved, including the desire for a more Western look.

One interesting picture I found that really deserves a mention was of Belkis Estrella Maldonado who is pictured in a prison beauty contest in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This demonstrates the global obsession with beauty, which is even able to infiltrate secluded areas such as prisons. It opens the question as to why women feel the need to get dressed up and perform even when they are locked up from the rest of the world. Maybe it’s just instinct or maybe the societal pressure to conform to the presentable ‘beauty’ standards remains? Although, I’m still not quite sure if I know the answer.

“Naomi Wolf once said, ‘Ideal beauty is ideal because it does not exist’ which I think was truly represented within this exhibition.”

Naomi Wolf once said, ‘Ideal beauty is ideal because it does not exist’ which I think was truly represented within this exhibition. Not only is the concept of ‘ideal beauty’ everchanging across different periods of history and cultures but it is also extremely hard to attain, which is why the cosmetic and plastic surgery industries are able to thrive as they profit off women’s insecurities who desperately try to fit into categories they have created. Have a rethink of the phrase ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’ because it’s more complex than we initially thought.

‘The Cult of Beauty’ is showing at the Wellcome Collection until the 28th of April 2024. The exhibition is free to attend.

All images sourced from: the Cult of Beauty exhibition