History Matters: Iran

By Jane Doe

Iran has recently been in the news, embroiled in a dizzying array of geopolitical events, tragedies, and exchanges. The progression of events has been rapid fire, difficult to keep up with and even more difficult to understand in a way that doesn’t perpetuate problematic biases or certain naivete pertaining to Iran. However, one cannot begin to understand, let alone contextualize and make nuanced, an understanding of present-day international relations with Iran without incorporating a critical, historical lens.

Most people think to the 1979 revolution and the hostage crisis at the American embassy as a, if not the, defining moment for the relationship between America and Iran. These events have set the tone for terse geopolitics between Iran and other governments, namely the US and the UK. I hope to explore what may be considered as a formative moment for Iranian foreign policy, in an effort to bring forward an understanding of why rejecting foreign influence is integral to the political identity of current Iranian leadership, and how this is related to recent, transpired events concerning Iran.

It is vital to understand what transpired before, during, and after the coup d’état in Iran because it sheds light on the tangled regime change efforts of colonial powers that have impacted Iran and various other countries in the region, and characterizes politics in and concerning Iran today.

Mohammad Mosaddegh may not be a name as widely known as Qassim Suleimani is now, but he was the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran from 1951 to 1953. In 1953, he was overthrown in a coup d’état that was orchestrated by the United States’ CIA and the United Kingdom’s MI6. It is vital to understand what transpired before, during, and after this coup d’état because it sheds light on the regime and the impact the colonial powers have had on Iran and various other countries in the region. This helps glean clarity into what characterizes politics in and concerning Iran today.

Both the US and UK secret intelligence services worked to bring down Mosaddegh because of his progressive social platform, which included nationalizing the Iranian oil industry. A more conventional portrayal is that the coup was related to the Cold War scare and communism. However, Iran’s decision to nationalize their oil was taken as a direct challenge to the world economic order at that time and the significance of this cannot be overstated. Their oil industry had been built up and controlled by the British via the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, now BP (British Petroleum). The arrangement of oil revenue was extremely one sided; Britain took 80% of profits, Iran received only 10-12%.

Iran attempted to negotiate a more equal power sharing agreement but broke off talks when Britain was unwilling and further denied Britain control or involvement in Iran’s oil industry. Mind you, Iran has 10% of the world’s proven oil reserves, they have discovered a new, 53-billion-gallon reserve, and they are currently the world’s fourth largest oil producer. This is no insignificant industry and, frankly, it has been a curse for Iran when it comes to the fervor of foreign interest in meddling with internal politics in order to control the oil.

Kermit Roosevelt Jr, a CIA official during that time, led the coordinated efforts to destabilize the Iranian government following its decision to nationalize their oil and after receiving a call from Britain for assistance in the matter. Without going into too much detail, a brief overview highlights the level of involvement of imperial powers in internal politics.

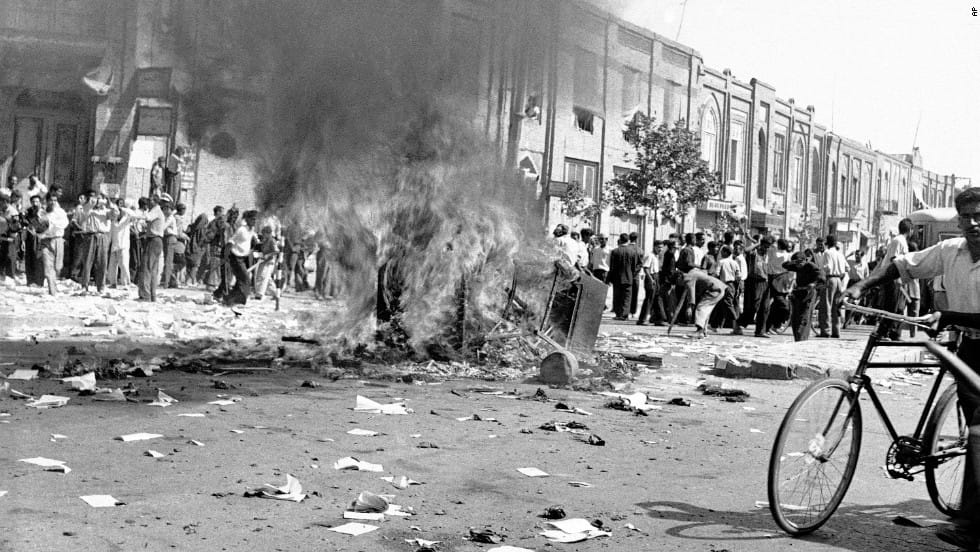

Kermit paid off Iranian media to publish and widely circulate anti-Mossadegh propaganda. Articles written by American CIA members involved in organizing the coup, under headlines claiming Mossadegh was an atheist, a Jew, and other allegations, were published in Iran specifically to undermine Mossadegh. The Islamic clergy was recruited to denounce Mossadegh through sermons. Kermit pitted Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who was the Shah at the time, against Mosaddegh through repeated secret meetings in taxis at night. Kermit paid one group of Iranians to engage in destructive activities around Tehran while pledging allegiance to Mosaddegh and communism, and then paid another group to attack the first group. The level of chaos was disorienting and created exactly the kind of conditions Kermit was intending.

The first coup d’état attempt was unsuccessful and the Shah fled to Rome, but Kermit succeeded on the second attempt. Mosaddegh’s house was bombarded, and he fled, later turning himself in and was put on trial for treason. General Fazlollah Zahedi, handpicked by Kermit, replaced Mosaddegh. Pahlavi was restored to his throne with consolidated power and ruled akin to a dictator, giving easy oil access that contributed to maintaining the economic world order until 1979. His subsequent overthrow in 1979 is for another exposé.

The takeaway of this piece should be that an understanding of what defines relations between Iran and the world is greatly enhanced when the political identity of Iranian leadership is contextualized instead of isolated and portrayed as seemingly belligerent, incomprehensible politicking. The 1953 coup d’état transformed the country and greatly shaped the foundations of politicking in Iran. For example, the 1953 coup d’état was used to justify, in part, the seizure of the American embassy during the revolution. The US bolstered Saddam Hussein in Iraq somewhat as a retaliatory move against Iran and subsequently funded both sides of the Iran-Iraq war which saw over a million casualties. In addition, the context of Suleimani’s assassination is not simply Iran-backed militia attacking U.S. military bases in Iraq, or Suleimani representing an “imminent” threat. President Rouhani issued a statement likening the action of Suleimani’s assassination specifically to that of the 1953 coup, crimes which “will never be forgotten.” The hypocrisy of internal politics, not to mention socio-economic conditions, and international policy of Iran is undeniable, and yet the impact of political identity on foreign policy and how that interacts with the high stakes diplomacy, negotiations, sanctions, and on-going threats of war must not be disregarded.