John Wilson on Public Broadcasting and the Culture of Culture

“So, yeah, I would say probably Radio 4 … is the single most important cultural resource in the country.”

by Gabriel Mullins, Culture Editor, BA History 09/12/2024

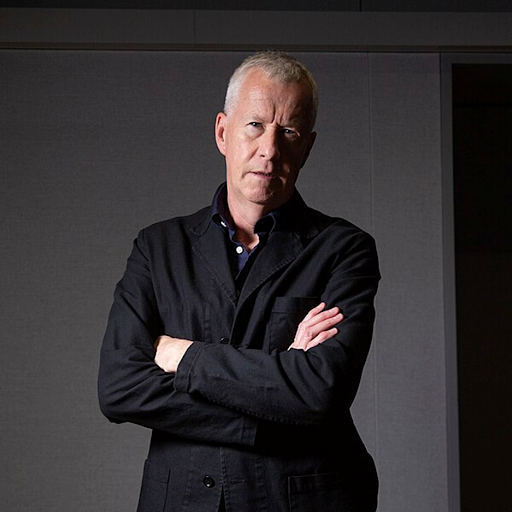

I sat down with John Wilson, veteran broadcaster and host of This Cultural Life on BBC Radio 4, to talk about how public broadcasters like the BBC make the ‘Culture of Culture’.

Wilson has a storied record in public broadcasting, which began when he joined the BBC in 1990, working on Radio 4’s arts series Front Row as a reporter and presenter from 1998 until 2021, as well as presenting and appearing on many other arts, culture, and current affairs programmes over the last three decades. He has presented the Radio 4 and BBC 4 interview series This Cultural Life since its inception in 2021.

In our exploration of the BBC’s role in creating culture, our discussion found its way from Paul McCartney to Hassan Nasrallah, from the difficulties in navigating the BBC’s mandated impartiality to whether the Beeb really does generate our culture, and whether it holds its strength as a media organisation designed to serve the collective. An edited and abridged account follows:

When you're choosing who to cover on This Cultural Life, what sort of editorial concerns do you have?

So the point of the programme is that it's getting sort of underneath the work. What is it that drives these creative people? The first person we interviewed was Paul McCartney. We didn't even put him first in the running order because it was almost like, where'd you go after that?

So we do a lot of writers, directors, artists, people who are very, very creative; the main thing is they have to be sort of top of their game, or leaders in their field, or basically have a really interesting story. So there are a few sort of lesser-known people that we've done, but generally they've got a really good story; we sort of know in advance how they've got that amazing story. So you have to look at it as a great story that needs to be told, because it's a 45-minute interview, which is, in Radio 4 airtime, relatively quite a long time.

Do you think BBC Radio 4, and other public stations like it, generate culture?

It does. I can't speak on behalf of Radio 4, because actually I'm employed by Radio 4 as a freelancer. But I do know that, if you look at the broader culture of Britain, Radio 4 is really central. You could sort of say that, for a long time, it's been very much kind of cosy and establishment-centric, but culturally it's just really important. It's kind of central to British identity.

You know, this is very much a middle-class identity, obviously, but this isn’t necessarily the case. If you look at the demographic of people listening to Radio 4, I think you can't argue with the fact that the majority of people probably live in the south of England and are middle class, but that doesn't mean they're the only people it aims to broadcast to.

In terms of generating culture, when we take out the news programmes, much of Radio 4's output is about culture. So, you know, that's book programmes, Front Row, film programmes, Screenshot, the Music Programme, Add to Playlist, and this Cultural Life and Desert Island Discs alongside a couple of other big interview programmes. But it's not just about the voices that you hear. Radio 4 does the BBC Short Story Award every year, it has the Radio 4 dramas, which it has done for years, and serialised books, which give a platform to new writers.

All of this is culture. It’s generating culture, and it's reflecting culture, and reporting on culture. So, yeah, I would say probably Radio 4, you could argue, is the single most important cultural resource in the country. The BBC is a crucible of culture.

As a journalist, what is it like to work within such a strict framework of impartiality as the BBC’s?

Well, you have to be absolutely, remain completely, or try to be impartial at all times. Especially if you're in News. Everything has to be balanced, which obviously is difficult when it comes to certain news stories.

For my work, it doesn't affect me so much. Although, I was presenting Last Word recently, which is the obituary program. We did Hassan Nasrallah, who was the Hezbollah leader. And there were lots of complaints on the BBC log.

I think people misunderstood the point of the obituary program. It’s not about celebrating great people necessarily, although often very much it is that, you know, because you've got a lot of sports stars or actors or whatever, and you are getting a sense of why they were special to people.

But it's the same in the newspaper, if it's somebody of note, of political or newsworthy importance globally, then you're marking their life and their death on an obituary programme. And it did obviously wind up a lot of people and of course, weirdly, it wasn't so much that we were talking about Nasrallah or celebrating his life, which certainly we weren't doing, it was about marking what he had achieved, you know, and the way that he had turned Hezbollah into fighting force. He was an absolutely staunch militant, and we made it clear that he was responsible for a lot of people's deaths.

And what upset people was that there was a full obituary for Nasrallah, but not for Maggie Smith, who had died the same week. And I suppose that you would have come to that conclusion if you were sort of half listening to the program and you heard it simply in that context, without realising the wider context, which is actually that the BBC had covered Maggie Smith in every sort of news out there.

Can a public broadcaster, though, with these kinds of constraints, ever be truly generative of culture?

Yeah, I think so. I mean, for instance, we've got a programme that went out recently with Peter Kosminsky, who's an acclaimed veteran maker of dramatised documentaries, or dramas that are actually based on facts. He made a film called The Promise. It was about a young girl who went on holiday or stayed with her cousin in Israel. Her grandfather in the story was a British soldier in ‘47, ‘48, at the time of the British Mandate in Palestine. And the story is basically about her uncovering her grandfather's story, which was seeing Palestinian people pushed off their land by Jewish settlers.

So, this was a contentious drama when it was shown. But the thing is, within the discussion that I did with Peter Kosminsky, I've still got to be aware that this is a Jewish filmmaker who is very, very critical of Israeli policy. Or, he created a drama which was contentious at the time because it was seen as very critical of the establishment, not the right for Israel to exist, but it was questioning the way in which obviously a lot of Palestinian people lost their land and the way that the state was established and the way that that had still played out to this day. While we were doing this interview, Gaza was being bombed, with thousands of people being killed, and with allegations of genocide. All of those things he is talking about, but I have to be aware as well that the response from some listeners is going to be, and I have to say, of course, you know, it's also about Israel asserting its right to self-defence, because Israel itself is under attack. We saw that on October 7th.

So it's just about creating that sort of framework within any kind of discussion which recognises that there are not just two sides to a story, and there are multiple perceptions.

Do you think within this framework of impartiality there is room for transgression?

Yeah, I mean, particularly within comedy. It's almost like it's ring-fenced. There's The News Quiz, on which you hear jokes about the Prime Minister, or government policy, which you are allowed to exaggerate for comic effect or to mock in a way that you wouldn't be able to do if you were reporting on the news. The BBC realises that people are clever enough to be aware of the difference between the joke and journalistic reporting.

Within general output, and I think I might be speaking out of turn here, but I think probably the BBC has had to be more cautious in recent years because it's facing an existential crisis. Probably not so much now with the Labour government and Keir Starmer proclaiming his support for the BBC, but you'll remember that when Nadine Dorries was the culture secretary, she was talking about abolishing the BBC, about wanting to cut the licence fee, which in effect is abolition. The fact that everybody who uses the BBC has to pay a licence fee means that you are accountable to a very broad populace.

People who are coming into adulthood now have grown up in a turbulent world, where public broadcasting may not have seemed to them a particularly effective model, or a particularly important part of their lives. How would you respond to this kind of scepticism towards institutions like the BBC?

I think a lot of the way the BBC is positioning itself is actually towards young people because, the thing is, without young people, what is in the BBC? It is going to struggle to survive, because without young people you're going to have that drop-off of people who don't recognise it, and then you’ll start to have a generation of people questioning why they pay the licence fee, because it's not for them.

You know, there's an amazing statistic, which the Director-General, Tim Davey, showed me, which is that something like 90% of the people in this country use the BBC at least once a week. The BBC is broadcasting to such a huge range of people, but there are a lot of people who will say, ‘I never use it’. If you ask them, ‘oh, you never watch Match of the Day?’ they’ll say, ‘Oh, I watch Match of the Day,’ and, ‘oh, you never watch Strictly?’ - ‘Yeah, I watch Strictly, that's all I do.’ You know, it's like, well, actually, if you watch Strictly, then, and you watch Match of the Day, then you are using the BBC. And the point is that it's such a broad church, where you're doing hard political programmes alongside, you know, 10-part dramas.

Lord Reith, the BBC's first Director-General, set out the organisation’s mission as being to "inform, educate, and entertain". These principles are enumerated in its Charter, and the ‘Reithian Mission’ is often associated with the historical idea of the BBC as an ‘elevating’ institution. Thinking about the BBC's role, as a public body, in making this country a better place, do you think that the Reithian Mission is still valid?

Yeah, the Reithian mission. It should be tattooed across my head. I actually do, because I think the interesting thing is that the BBC, for all its faults, and it has many… But actually, you know, a lot of its supposed faults are because it's trying to do the right thing very often. What it is trying to do... is sort of swimming against the tide of what is happening politically. The public service remit of the BBC used to be something that was actually shared by a lot of broadcasters. It was a kind of an obligation to have news on the hour, even if you were running a rock and roll station.

There are so many outlets now that are so commercial, especially with the rise of podcasting, where you don't have the same editorial controls. In a way, that kind of makes the BBC slightly hamstrung. It means that you can't go out on a limb with certain things. You have to be careful of platforming certain people. You have to make sure that everything politically is balanced, particularly in election times or within contentious issues. It's very, very difficult, I think, for the BBC.

But I think if you joined here as a young trainee, if you joined the newsroom, it would be absolutely instilled in you in your training, the Reithian mission. I think it still stands up. I think that the BBC is almost now kind of alone in the world, really, as an organisation which adheres to such obligations of impartiality and strives to be the voice of objective reporting. Probably, there's a lot of reporting that could be very frustrating, when you're seeing things play out, which actually, politically, you feel some affinity to, or you feel absolute abhorrence towards. You have to remember that your personal opinions don't come into it. You have to be reporting objectively what's going on. So I don't think that's really changed.

As much as it drives me mad you know, because it's a really fucking frustrating place to work in, because it's so big and there's lots of layers of management and it's very difficult to get things done and, you know, all of that can be incredibly frustrating. But the reason sometimes the BBC takes so long to get things done is because it actually likes to do things properly and, if you rush into things, mistakes get made. So it kind of works two ways. Even though it can be an incredibly frustrating place to work in, I would always defend the BBC and I would hope that it would survive in its current form.