Lebanon’s Grassroots Solidarity in the Face of State and Foreign Abandonment

'100 years of history and fond memories erased forever. The heartache impeded on us has reached our grandparents' cemeteries, which were not spared from the shelling.'

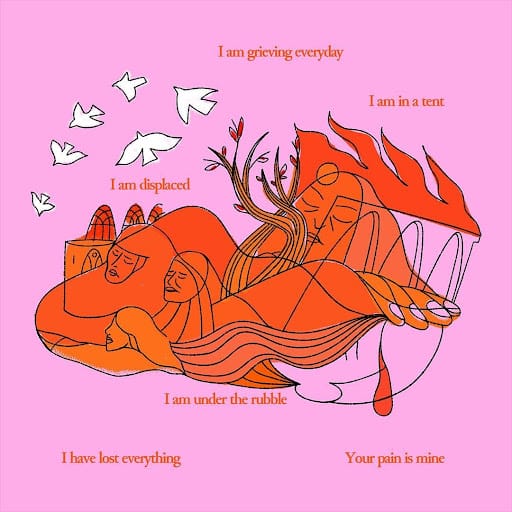

by Petra Y. Fallaha, BA History of Art 09/12/2024

On 23 September 2024, Israel launched 200 airstrikes across five Lebanese governorates, resulting in 569 fatalities, including 50 children. This came just days after a coordinated attack on 17-18 September, when hacked pagers exploded across Lebanon, killing 39 people and injuring 3,400, mostly civilians. The escalation intensified on 27 September with the assassination of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and other senior commanders. On 30 September, the Israeli Defence Forces launched a ground invasion of southern Lebanon, marking the start of the war.

As of 20 November, the death toll has climbed to 3,600, including 230 children, with over 15,000 injured. The humanitarian crisis worsens as winter approaches, with at least 1.2 million civilians having been displaced from the South. Ayla Mortada, a Lebanese illustrator who has family in Nabatieh, reflects on her family’s displacement:

“My relatives were the last people to flee their home in Nabatieh, my great-grandmother’s house. We’ve been there before, for decades, we’ve always returned to our land, rebuilding what was destroyed, but we’ve never experienced the destruction of our homes, down to smithereens. 100 years of history and fond memories erased forever. The heartache impeded on us has reached our grandparents' cemeteries, which were not spared from the shelling.” Refugees fleeing conflict from neighbouring countries and foreign domestic workers who came seeking a better life now find themselves struggling once again to survive. Photographer Raghed Waked shares his experiences up until now with the war:

Tell me how you started photographing Israel’s war on Lebanon.

“I used to work as a nightlife photographer but became unemployed because of the war and needed to make money. I started doing interviews with people who lost their homes and lives. I covered a funeral for a journalist killed by Israel. I covered a shelter hosting 200 female workers from Sierra Leone and Sudan. A lot of foreign workers based in Dahye (Beirut) and Jnoub (the South) were abandoned by their employers. Some people said, “Our boss locked the door on us and we were abandoned at the house, we had to jump out of the window and escape Dahye.” The Lebanese people are helped first, then the others. There are workers who escaped the war in Sudan, which is a lot worse than the war here. They can’t go back home but they can’t stay here because they have no job and nothing to do.”

Were these some of the scenes that struck you the most?

“The story that struck me the most was from a 7-year-old kid coming up to check on his Uncle's house which was incinerated to dust. Another is when Israel bombed an area in Dahye causing huge fires. One of the buildings went up in flames with the concierge still in it. The explosion was so strong that they couldn’t find any traces of him, he became ashes. The son of the concierge went into the building hoping to save his father but died trying to find him. We went into this area to take pictures and listen to their stories, it was horrible.”

Yet, the community is still finding ways of helping. Maya Ayache, a cook now coined as the “Mattress Queen” has been supporting displaced families as the winter fast approaches. After resistance fighter Hassan Nasrallah’s assassination, followed by Israel dropping 900 kg bunker-busting bombs on four residential buildings, Maya was forced to flee to her village as the situation grew more unstable. “That was when I was motivated to start collecting mattresses, blankets, and pillows. Countless people began calling me, talking about the displacement of their families and what they needed for shelter. I’d write down their names and make my way from the village all the way down to Mkalles, closer to the capital, to distribute donations. From the moment I wake up and open my eyes, people are calling me. A lot of them have been displaced twice; this one taxi driver showed me his house in the village reduced to rubble. A lot of people have newborn babies–a lot of different heartbreaking situations people are dealing with. I don't know what the government has handed out, nothing I think. But we’ve handed out a lot, and I don't know how long I can go on my own with this operation.”

As the country’s instability grows, people like Maya become limited in what they can do to help. There is an overwhelming consensus that the growing demand for support can only be fulfilled through foreign and state intervention. All of the testimonies gathered here speak out to the international community urging for their help.