Lee Jong-pil’s Escape: No End to Capitalism

"Despite the film being introduced as a drama/action, Escape played out as an absurdist horror, peppered with strategic moments of comic relief"

by Amira Berdouk, BA Korean 09/12/2024

SPOILER ALERT

In baggy jeans and a fluffy, offensively multi-coloured fleece, I met my brother outside the Odeon Luxe Cinema in Leicester Square for the Opening Gala of the 2024 London East Asian Festival (LEAFF) on October 23rd 2024. We were greeted at the door by staff and directed to the upper level circle. Just before the theatre doors was a group of giddy attendees, clad in black tuxedos and glamorous evening gowns, all trying to steal a picture with the celebrity awardees of the night, Sandra Ng and Lim Ji-yeon. Suddenly very aware of my outfit, I realised my brother and I would be diversifying the audience demographic of this event quite a bit.

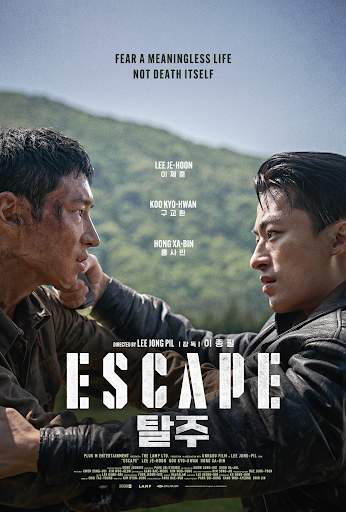

Before ordering the tickets for this event, I was at once excited and curious as to how the feature film would play out. Escape (탈주) by South Korean director Lee Jong-pil (이종필) is a 2024 drama/action about a North Korean soldier nearing the end of his ten-year-long military service close to the Korean Demilitarised Zone (DMZ), attempting to defect to South Korea. Although I found the general premise of the film to be very interesting and centring a globally pertinent issue, a film about a North Korean defector produced by a South Korean studio made me approach the screening with a somewhat cautious mindset.

After a confusing yet surprisingly moving organ performance and awards ceremony, Director Lee Jong-pil introduced the opening film with a sincere note. Lee expressed the production’s intentions as an attempt to spread awareness, and acknowledged the film’s cultural and political positionality as South Korean-made. Two possible outcomes came to mind during Lee’s opening speech: (1) Escape would be a touching ode to Korean solidarity, and/or (2) there may just be a little too much anticommunist sentiment for Escape to ‘spread awareness.’

As the ending credits began rolling, a round of booming applause engulfed the theatre. Escape felt like a film that successfully grasped the viewer’s heart, teasing with palpitations of horror and halting twangs of empathy. However, in retrospect, I can now assess my viewing of the film with a less reactionary, somewhat more objective lens.

Despite the film being introduced as a drama/action, Escape played out as an absurdist horror, peppered with strategic moments of comic relief. Human survival and the lack of civilian autonomy imposed by authoritarian states, such as the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), are not themes to be taken lightly. Unlike many commercial action films that deal with generic patterns of conflict and resolution, the true horror of Escape seems to lie in the ending that saw no resolution to protagonist Im Kyu-nam’s defection to the southern neighbouring state, the Republic of Korea (South Korea). The external conflict of life in North Korea seemed to be merely transferred to an internal struggle once south of the DMZ.

Almost immediately after leaving the venue, I jumped online to read reviews and debrief with my brother on the way to dinner. At a respectable 3.4 stars on Letterboxd, online reviews remain notably mixed, as to be expected for a film dealing with the politics of the Korean partition. Viewer reactions ranged from denouncing the film as ‘at the very least, watchable’ anticommunist propaganda, to hailing the continuous levels of tension as ‘superb’ and ‘compelling,’ to humorously interspersed comments of antagonist Ri Hyun-sang’s neglected gay subplot. And yet, to some extent, I find myself agreeing with all of the above.

The cast of Escape is filled with a myriad of skilled actors, such as Koo Kyo-hwan, Lee Je-hoon, Lee Ho-jung, and Song Kang. A stunning soundtrack, impressive camera work, particularly shown in a tantalising tracking shot where protagonist Kyu-nam and accomplice Gam Dong-hyuk run away from State Security in a field of tall grass, while the camera is fixed before them so that the audience’s breath stops short when the two hopeful escapees leap off the edge of the grass into an unknown opening.

Early on in the film, before Kyu-nam had begun his official attempt to escape, he is stationed at a watch tower in the DMZ. A small radio with access to a nearby South Korean radio station plays the song Yanghwa BRDG (양화대교) by Zion.T. This R&B song, with a beautiful melange of nostalgia and optimism, cuts through the solemn atmosphere of the small military watch tower. Yanghwa BRDG would become our protagonist’s anthem, igniting his subordinate Dong-hyuk’s courage to implore Kyu-nam to bring him to South Korea in order to reunite with his mother and sister.

However, as the film progressed, director Lee’s plot seemed to be littered with many loose ends, frayed and begging to be tied up. To begin with the least consequential of plot holes, the film’s antagonist, State Security Officer Ri Hyun-sang who later becomes obsessed with the pursuit of ‘deserter’ Kyu-nam, is heavily implied to have been in a relationship with another man during their time abroad in Russia. However, it is revealed around the same time, at an official celebration for Kyu-nam’s capture of his deserter accomplice Dong-hyuk, that Officer Ri is married and expecting a child. While Officer Ri socialises with a crowd of women at the centre of the ball, all of whom enthusiastically congratulate and ask after his absent pregnant wife, Officer Ri’s past love interest, Seon Woo-min, lingers on the periphery of the social gathering. Woo-min is played by Song Kang, an actor best known for his work in a plethora of romantic Netflix series as well as popular horror drama Sweet Home. The two continue to share knowing glances from across the room throughout the event. At this point, I am unsure of the number of times my brother and I had turned to each other, confused as to how this would impact the trajectory of Kyu-nam’s escape as well as the overarching plot of the film. Disappointingly, apart from a brief interaction between the scorned exes and a relatable spiteful nickname for Woo-min in Officer Ri’s smartphone, nothing came to fruition between Officer Ri and Woo-min. Besides a briefly implied flashback of the two having been romantically involved during their shared time in Russia, not a single development was made.

Elsewhere, my interpretation of the ending of Escape still fluctuates to this day. Although many reviews were ready to label this film as outright anticommunist propaganda, I find it difficult to agree. The ending of Escape does, indeed, see Kyu-nam escape to South Korea, but he is troubled by an internal struggle. A void remains wide open in our protagonist’s life, even if he can now have the ‘freedom to fail’ in a capitalist society. Neither was this ambiguously suggested, but was clearly expressed in the ending scene where Kyu-nam admits to this feeling of unfulfillment and dissatisfaction. We see Kyu-nam in South Korea as a healthier, seemingly wealthier version of himself, with fuller cheeks and the iconic South Korean bowl cut. His financial and housing situations are conveniently left unspoken of, although he seems to be very comfortable writing a letter to a radio station from a desk in what must be his new bedroom.

The ending scene of Escape shows Kyu-nam walking into the night on Yanghwa Bridge, the title of Zion.T’s feature song. I recall thinking that this may be the first time Kyu-nam was shown walking leisurely, not running for his life from State Security or camouflaged by fifty other men marching in line. Therefore, I cannot help but feel that for the duration of the film, Kyu-nam’s tireless efforts to escape the North Korean military is a projection of the capitalist South Korean imagination. His escape was so vividly depicted, step by agonising step, yet Kyu-nam’s supposed safe haven in the south is mystical and, at most, vague. As he walks off slowly into the night across Yanghwa Bridge, Zion.T’s song perfectly encompasses the new struggles Kyu-nam will face in South Korea: ‘let’s be happy, don’t hurt’ (‘우리 행복하자, 아프지 말고’).

Kyu-nam admits in his letter to the radio station that he hasn’t yet found happiness, but he now has the freedom to fail. Despite this message of progressive optimism, the image of Kyu-nam walking into the darkness of Seoul’s evening seemed aimless, another loose end. Only this time, Kyu-nam has no plan, no map to find his happiness. This idealised aimlessness seems more like a distraction from South Korea’s indefinite future as a capitalist society, like many other countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), struggling with endless socio-economic issues such as a soon-to-be super-ageing society, low birth rates, and a vast economic inequality paradox. I think we can all agree, ‘let’s be happy, don’t hurt.’ But, who will draw the map for South Korea?