Misguided Solidarity or Perverse Late-Stage Capitalism: Corporations Engaging with Public Activism.

Millie Weighton Glaister, BA Politics and International Relations

When you see companies or brands online attempting to engage with niche internet humour, from Twitter beefs between fast food companies to Ryanair on Tiktok joking about their charges for extra baggage, it raises a level of dissonance.

It is almost fine, but at the same time there is a nagging feeling that you are being manipulated. I believe this phenomenon is exemplified by brands executing public displays of so-called solidarity. Whether adding Black Lives Matter to their Twitter bios or slapping a pride flag on their product, companies are evolving to incorporate appropriated language of solidarity into their marketing campaigns.

However, when it comes to public advocacy, the stakes are much higher than feeling tricked by a marketing tool. The heightening of this insincerity comes from the fact that it is not simply whether a company has improved their public image from a cheap laugh.

Rather, insincerity arises when a company can raise public perception without making any substantiation to their support and oftentimes continuing to benefit from the exact inequalities they claim to stand against.

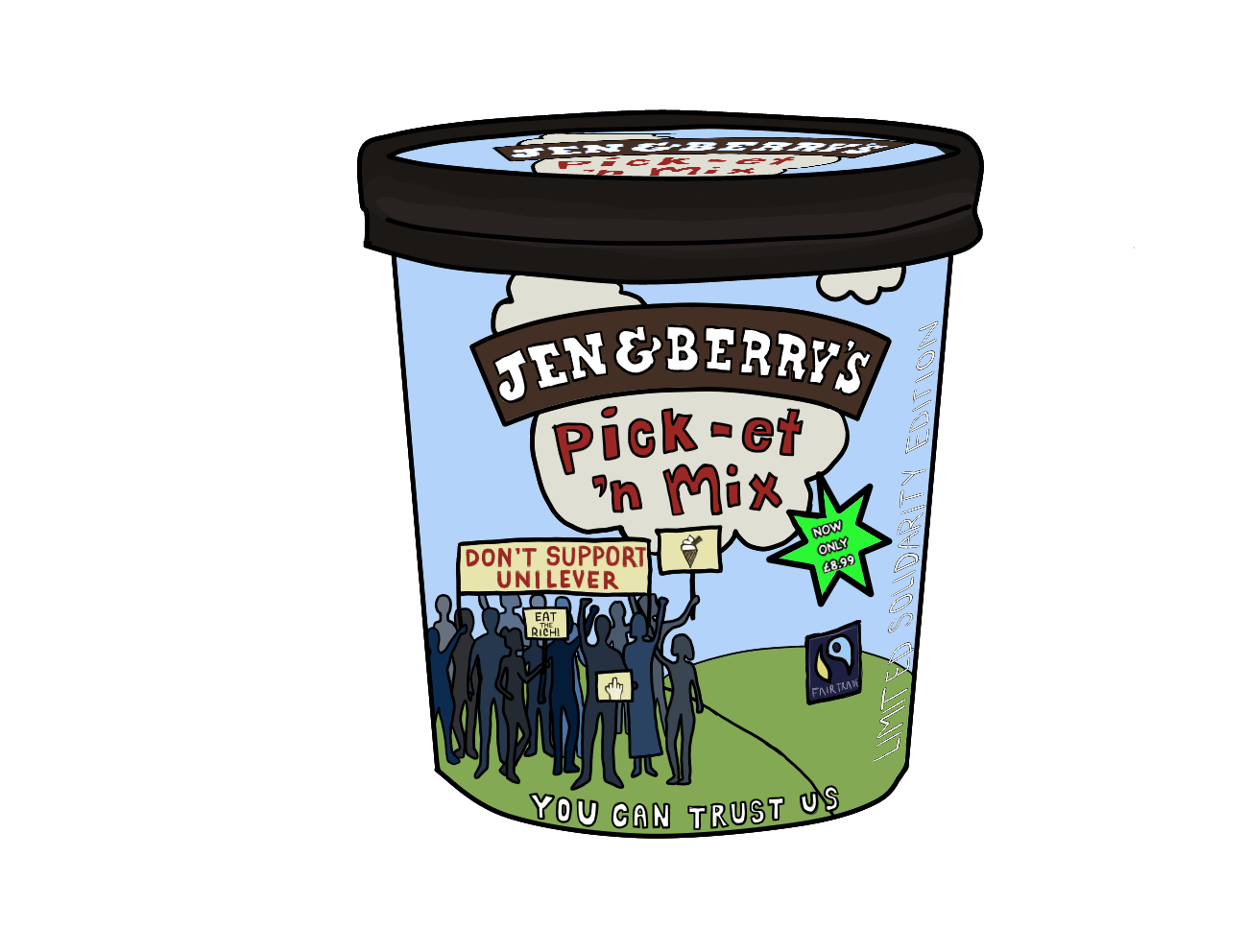

Ben and Jerry’s has always been well versed in incorporating social movements, with speciality flavours such as Change is Brewing to support ‘safety and liberation for all.’

Despite their continued support for societal reform, the company was acquired by Unilever in 2000. Unilever has been subjected to accusations from environmental pollution to human rights violations, demonstrating that they can profit from the public political image of Ben and Jerry’s without incorporating any of those values into their wider organisation.

Similarly, Nike has benefited enormously from public advertisements endorsing social change, such as their feature of Colin Kaepernick after he took a knee to highlight police brutality and racial injustice which resulted in the loss of his NFL contract. Yet again, this was accompanied by voices within the company demanding that internal issues with a lack of diversity and representation of people of colour in leadership positions be addressed first.

Kellogg’s had the spotlight in 2016 for removing their adverts from a right-wing news site, Breitbart, stating that the site didn’t ‘align with our values.’ However, despite these self-proclaimed values, they were unable to support their workers’ demands in contract negotiations, resulting in a strike of 1400 workers. During this strike, Kellogg’s went even further and attempted to hire permanent replacements for striking workers.

It doesn’t take long to discover the farce of public displays of solidarity such as these; it becomes apparent very quickly that there is little effort made to incorporate substantive changes alongside their marketing ploys. Some companies do, at least monetarily, benefit causes. For example, Absolut’s partnership with LGBTQ+ charity Stonewall, and their support through their Pride edition vodka bottle.

“Can companies engage with solidarity in a genuine sense or is it always just virtue signalling?”

However, it is impossible to separate those benefits from the capital gains that ensue; there is no definitive way to determine their motivations. It raises the question: can companies engage with solidarity in a genuine sense or is it always just virtue signalling?

It appears that consumer power has dictated a society where political engagement is expected from corporations. However, this raises yet another question of if we can demand their engagement, why have we not been able to demand the structural change that should accompany it?

Fundamentally I think this comes down to the capitalism of it all: the public displays of solidarity win in their cost-benefit analysis. They stand to lose very little, bar a few individual consumers. However, the structural issues of capitalism – the exploitation, the ingrained discrimination, the rampant inequality – are how such corporations can maintain their immense profit margins.

To change any of these conditions would cost the company and potentially cost those in charge their power. When it comes down to it, a capitalistic enterprise will prioritise profit over anything else, including the rights and safety of its consumers and workers.

Solidarity here has been commodified and turned into a transaction, whereby there is a culture of fear for not speaking out, but there is no requirement to go beyond releasing a statement. This breeds performative activism that undermines what true solidarity is.

Coming to this conclusion lands us in the discussion of late-stage capitalism, in which the depths of inequality created have changed the way consumers engage with businesses. Essentially, capitalistic corporations must engage with the very issues they depend on to survive. Thus we end up with brands as evil as can be (Amazon) releasing statements on the importance of the Black Lives Matter movement: a veritable capitalist hellscape.

This analysis doesn’t limit itself to corporations or brands, it runs through every institution where profit plays a role. To bring it closer to home, SOAS itself is guilty of this very phenomenon.

I certainly made my choice of university-based on the reputation of SOAS as a left-wing and just a fundamentally good institution – how naive I was. SOAS actively perpetuates this idea and yet it took less than a term of being enrolled to become aware of the structural issues that lie so close to the surface. In a recent press release, SOAS has referred to their ‘broader social justice agenda found in the institutional community pillar of the new strategic plan.’

The truth is that SOAS is supporting Adam Habib as the director despite his use of a racial slur in an all-school meeting in 2021. They are failing to support academic and support staff resulting in strikes while continually shrinking the departments that they claim to champion. The list goes on.

In their drive to make SOAS a profitable institution, they have failed to address the real issues that affect students and staff alike.

While all of this seems unchangeable and frankly quite depressing, we are not out of options yet. The only practical solution I can see is to make it unsustainable for institutions and companies to continue like this.

Until we can revolt out of this capitalist society, we have to engage with them in a language they understand – profit and power. We must utilise our collective consumer power and demand that organisations actually commit to making structural changes, and be ready to enact our threats if need be. If companies want to benefit from appropriating solidarity, let’s hold them accountable and demand that they actually represent that change from the top down.

Photo Caption: The Pride edition of the Absolut Vodka bottle (Credits: Absolut Vodka)