Shades of Identity: Unveiling the Liminal World of London's Mixed-Race Women

By Nathan Hay, BA Social Anthropology

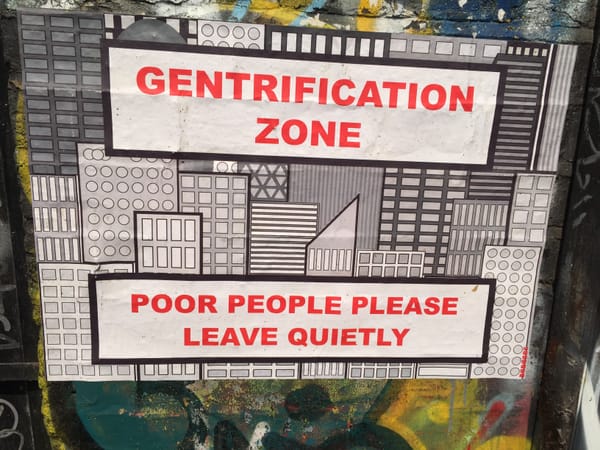

London is a melting pot; one where the experiences of young women navigating layered racial identities are often overlooked. Mixed-race women have a struggle of their own that is grossly understated in public discourse. I set out to have conversations with several women (of Black and white descent) in order to get a better understanding of their nuanced positionality.

We’re told we ‘shouldn’t assume’, and yet people still do. Specifically, people tend to guess and label individuals with particular racial identities. An extension of this assumption is that someone may be more likely to have ‘easier’ life experiences; such is the meaning of ‘passing’. More than anything, it highlights how mixed-race women are pressured to choose one racial identity over another to fit into society.

One woman spoke of being driven towards one race by some but not fully being accepted by those in said race, saying that, “if you’re not passing as the bare minimum, you are Black”, and is often perceived as Black by white women when with her Black friends. Another said, “I’m always just counted as a half… and I don’t really know how to feel about that”. Describing their personal experiences, most of the women I interviewed spoke about not having a strong place of belonging, with another saying: “I don’t feel like I fit in with the Black girls necessarily, not to say that they weren’t welcoming and they weren’t all lovely, but there were just certain things that they would talk about that I couldn’t really relate to, so I just never knew.” Being caught between two racial identities, but never fully belonging to either is a challenge. The norm either consists of an innate feeling of being something ‘other’, or an aggressive shunting into either side, neither of which is comfortable.

The experiences of the people I interviewed are shaped by gender as well as racial dynamics. Some of the women picked up on the perception and expectations that many men in Black communities have of women: “[they] have a strong idea of what roles women should play in life in general.” This links to their cultural backgrounds, in which “the man goes to work and the woman is more in control of the kids, the house, the cooking and the cleaning”. Being the skin tone you are when mixed-race, seems to have made no difference in removing this stereotypical gender role, as it appears to be more rooted in culture than anything else.

“I’m always just counted as a half… and I don’t really know how to feel about that”

One woman noted that “Black men and white women have this subconscious outlook that they are one below being a white man so they tend to step on those who are below them (i.e. black women)” – multiple women exemplified much of the direct sexism they’d faced to stem from Black men in academic and work environments. From what I gathered, the experiences of a mixed-race woman in London regarding men stem from a perception of them as Black, as well as gender roles commonly found in African and Caribbean communities. As a Black man in a Black household, I see these cultural affairs reflected in many aspects of Afro-Caribbean life, and further investigation into other Black men and women’s lives led me to the same conclusion. Evidently, gender roles and their rooting in an outdated culture play a huge part in a mixed-race woman’s life.

The experience of being mixed race is shaped by a range of factors, including family dynamics, cultural context, and societal attitudes towards race. Regarding family, one woman expressed that, “having a white mum and Black dad means that neither of them truly understand my experience, which results in a lot of arguments.” She then went on to speak about a recent argument on cultural appropriation wherein she tried to teach her mum the importance of understanding it. She shared that her mum had grown up largely around Black people and had “almost forgotten her own whiteness.” She stated that her dad “clearly has a lot of internalised racism and often puts down other Black people to defend white people,” which resulted in her mum invalidating her Jamaican heritage due to the lack of Patois she speaks and the lack of Jamaican food she eats, despite having grown up with two very British parents who never went out of their way to exposure her to Jamaican culture.

Ultimately, the argument showed that as a mixed-race person, you can be othered even within the vicinity of your own home, as neither of your parents have completely relatable experiences to you that they can teach from. Though this is by no means a universal experience amongst all mixed-race women, the racial divide present in mixed-race households between parents and their children uniquely has the potential to bring misunderstandings and tension into the mix. As a result, neither parent is fully able to relate to their child, and the child is devoid of a living environment in which they can be entirely understood.

The general consensus showed that as a mixed-race woman, “you are never white enough or Black enough to be considered either” unless it fits the interests of the considering party. Some of the women I spoke with described feeling pressure to choose one racial identity over the other, whilst others felt that they were able to embrace their mixed heritage and find a sense of belonging within this identity. At the end of the day, the message still stands: the mixed-race woman’s experience deserves and needs to be heard.

Photo Caption: The multichromatic nature of the women of London (Photo Credit: Metro.co.uk)