"The Orange Trees of Baghdad" - a conversation with Leilah Nadir

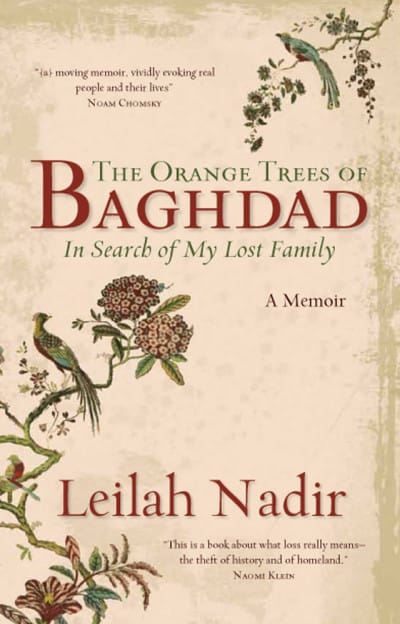

“The Orange Trees of Baghdad” is Leilah Nadir’s first book, a haunting memoir of a Baghdad she never knew, but which filled her life through the stories her family told her. Set against the backdrop of the Iraq war, the book brings a different perspective on Baghdad’s fate.

We reviewed the book here, and have also managed to sit down with the author for a quick chat.

By Beth Jellicoe

Tell us about “The Orange Trees of Baghdad”.

It is a memoir about my family. My father’s Iraqi, my mum’s English, and he left Iraq in the 1960s to come and study in England. That’s where he met my mother. So the book is my reconstruction of his life and his family and history through my eyes, through the stories that he and his family have told us. And at the same time it’s a description of the invasion of Iraq, and what happened to me and my family both in and out of Iraq while that was happening, and in the aftermath. So it’s a reportage of the war, seen from the diaspora.

Was there something that prompted you to start putting the book together?

Yes, I had been wanting to be a novelist and I had written a lot of fiction, but I hadn’t published anything in book form. And so I’d never intended to write a memoir, especially at the age I was – I was in my mid-thirties and you don’t feel like you’ve had a life to write about. But just as the build-up to the war was happening, I had started to communicate with my relatives in Baghdad, which we hadn’t really done that much before. There was a lot of worry about them, and what they were going to do. So I started talking to them and I realised they were stockpiling food, they had already been through two wars and the sanctions, so they already were very exhausted people. And the contrast between talking to them, and talking to my great-aunt – who was single and living in the family home on her own – there was a contrast between her personal story and what I was hearing on the news every day, which was all about Saddam Hussein, all about military build-up, whether there were WMDs or not. And it just seemed so far removed from the reality of Iraq that I knew. Which was, this was a country that was poverty-stricken, on its knees, and Saddam was neutralised. There wasn’t a threat. But also there was no voice or representation for Iraqis, anywhere in the West. We didn’t know Iraqis, we didn’t care about them – and that helped the propaganda. Because the politicians, the people who started the war could paint whatever picture they wanted of the society.

My family’s Christian – the big Christian community there, no one ever talked about that. It was always ‘people of an alien religion, in an alien country!’ And it made me so angry, so all I could do was write. And I started taking notes when I was talking to my relatives on the phone, and gathering more and more of this stuff, so I decided I wanted to get it out there. And so before the invasion, maybe a week before, I did a commentary on the invasion about my family. And then the day the war broke out, an article I wrote came out about my family, and what they were doing to prepare for the war. So it was too late.

You were living in Canada at the time?

In Vancouver, yes.

Do you think ordinary Canadians believed the propaganda without thinking about it?

There was definitely a split. Canada didn’t go to war, there was a lot of activism against the war, and it had a good effect. Who knows why they didn’t join the Americans, but it was pretty surprising. In the build-up, I felt like a lot of people were pretty confused. “Should we go? Saddam’s a dictator, we want to get rid of him, he’s a horrible man.” There was that argument. But then there was this sense that people knew that the argument that was being made on the Bush-Blair side was not very solid. So I felt that there was a mix. You’d go for a walk in the park and hear people debating heatedly. But I always felt it was abstract, it was never really thinking through the fact that we were going to drop that many bombs in such a short time on a population who’s stuck and cannot move. We’d done it in the Gulf War, but this was on a huge scale.

You talk a lot about your generation in the book. What do you think about the new generation of Iraqis?

The ones I have come across who have left Iraq – the trauma is still catching up with them, I think. Once you have to start your life in a new place, you have no time to really reflect. I have seen writing done by young people who expressed a lot of anger at what happened to them. So I think there’s a psychological processing they need to deal with. And they’ve really lost their whole country forever. They will not go back. And the Christian community was eviscerated. Once it was around 10% of the population and now it’s 1 or 2%. So all those people have left. From what I hear, the whole of Iraq’s society has changed dramatically. There’s very little middle class, there’s no professionals. You’ve got the political elite, and the poor people who couldn’t leave. Anyone who’s stuck there and in between is living a very different life from their parents.

Do you think there’s any way Iraq can recover from that?

I spoke to an Iraqi woman who went back last year. She said: “Before I went to visit, I thought it might take 500 years to recover. But now I’ve been there, I’m going to say a thousand.” She said the city was unrecognisable. She didn’t know where she was. She used to dream of Baghdad nights, but since she went back there’s so much pollution that she can’t see the sky any more. People don’t want to hear that, but it’s how Iraqis feel.

In the UK Iraq gets talked about as though it’s ‘our’ tragedy, of being pulled into an illegal war and being lied to. We tend to make it all about us.

And not about the Iraqi people.

There’s still a lack of accountability.

Huge. There’s no accountability. Has anyone been punished for lying? To the whole world? About something as important as war? This is a massive thing. And even us as a culture, meaning North America and Britain – we have not demanded that as a culture out of our leaders. We’ve allowed it to continue. I think the beauty of it for them is that Obama can leave and say: “We’ve pulled out, the country is on its feet, now any problem it has is the Iraqi government’s fault.” And it’s very nice and clean, but it’s not the truth. The truth is, the country was destroyed by the West, and it cannot come back by itself. If you compare it to Germany after the war, they got massive help to rebuild. And we got nothing.

Before the war there were huge protests on February 15th. I think those people lost a lot of hope when there was such a huge worldwide protest and it made no difference. And if only those people could be reignited again, and realise we have to have that accountability, or it will happen again. Maybe not right now, because we would protest now, but maybe in 10 years they would do it again. When people have forgotten. I wish we had someone who could lead that charge.

You talked a lot in “Orange Trees” about being an immigrant. What’s your relationship to Iraq now? How do you feel about your status since writing the book?

I was afraid I wasn’t Iraqi before I wrote the book, because I haven’t lived there. And even though I know the culture, I don’t know the language – I felt I wasn’t allowed to be this. I felt it very strongly. But since writing the book, and being received by Iraqis, I’ve realised I am Iraqi, and they’ve embraced me as one. And I feel like that part of me has melded together. I still haven’t been, but I can stand up and say: “Yes, I’m Iraqi.”

And it’s been wonderful when Iraqis have read the book, and they’ve said “I feel like you’ve captured Iraq. You’ve captured what it was like before.” How is that possible, when I haven’t been? But somehow, I have absorbed it, the stories and the people and the culture. And people are essentially a country. It’s the people that make the place. All my family had to sell their house. They are all out of Iraq now.

And that house had been in your family a long time.

Sixty-five years. They all say it doesn’t feel like they’ve lost a house – it feels like they’ve lost a country. And now all that’s left is the book, for me to tell my children about our history.

Last question: do you have plans to write a sequel?

Not a sequel – unless I somehow make it to Iraq – I’d have to write something about that. If I went back, I would be describing a whole new place. But at the moment I’m working on a novel that’s set in Iraq, but in the 1920s, under British occupation. It’s set in Iraq and London, with some historical characters and some fictional. And that is really pleasant to work on, because even though it’s also set during a war, there were a lot more positive things that came out of that experience. I wanted to explore more cross-cultural pollination that was positive, so that’s been really good. There’s very little written about that time from the Iraqi point of view, so I feel frustration about “How am I going to get into the heads of Iraqis from that time?” So I’m drawing on some of our family’s stories, but that’s when my imagination really had to step in. I do believe in ancestral memory and in blood, and in connections to a place.

“The Orange Trees of Baghdad” is now out in bookstores.