The Plight of Freedom

Racha Sobratee, BSc Economics

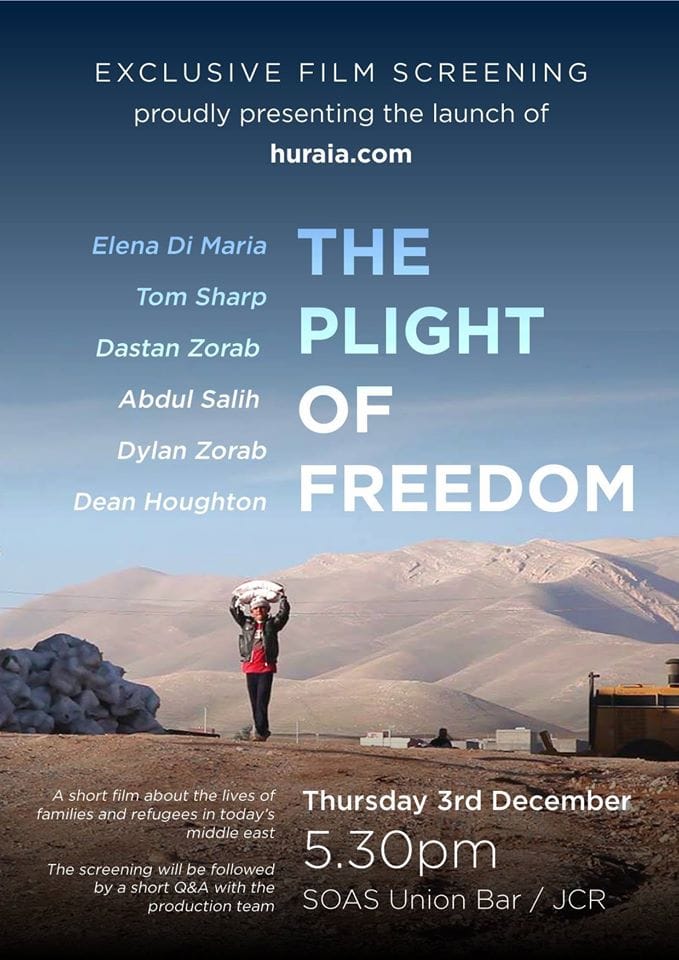

SOAS students have collaborated to found a new online platform, Huraia, publishing articles discussing the wider MENA (Middle East North Africa) region. To celebrate the launch of Huraia, the JCR hosted a screening of a rough cut of a short documentary film, which will go on to be edited and released at film festivals.

‘The Plight of Freedom’ highlights the extreme lengths that the families escaping persecution in the Middle East have to go through. This is explored within 3 refugee camps in Kurdistan, with stories shared from regions around Syria and Iraq. Recent events in the media have lead to a global prejudice against refugees, and the film offers an insight into the personal stories of the people who do not have a platform to represent themselves.

The screening was followed by a Q&A session with the crew members:

What inspired you guys to do this project?

For us we knew that we had a chance to show a different side. We just wanted to give people the other view, the other side that isn’t covered. To show people that these are real people like us.

A lot of Dastan’s family are from Kurdistan and have been refugees in the past. Having grown up around refugees and knowing that there’s animosity and a prejudice towards refugees which isn’t true and that the media are fuelling it made us want to challenge that.

What was the biggest challenge for you as a crew?

The biggest challenge was probably children, as soon as we put up a camera we were surrounded by children who wanted their photo taken or who wanted to be on camera so getting shots was a difficulty!

The psychology behind the filming [was a challenge] as well. You’re really focused on getting the right shots to make it look right, but you get to the realisation that you’re there for 10 days and you don’t know these people and it feels like you’re intruding on their life. But you have to distance yourself and understand that this film can only make the situation better because people don’t understand their situation at all. They only understand what the mass media is telling them which is there are sociological issues and not psychological issues.

Are there a lot of charities in the camps? What are the biggest challenges facing the refugees in the camps?

Right so we went to three camps. Barika is one that takes in Syrian refugees when they come to Iraq, so they’re managed by the UNICEF, International Rescue, and other local charities in Iraq. But the other two are IDP camps which is internally displaced people so they’re from other areas in Iraq, and according to Iraqi law, those refugees are the responsibility of their government, the Iraqi government. But the situation in Kurdistan at the time, and probably still, is facing an economic embargo from the government – so they’re not giving them any money. So the people who get stuck in the middle of this are the refugees form other areas in Iraq who are not getting any money towards tents, towards food – and it’s all political.

How safe did people feel in the camps?

I think a lot of people felt fairly safe, especially in Kurdistan it’s a lot safer than other areas of Iraq, and the areas they escaped from are their comparison, so I think they felt fairly safe. The bigger concerns were about equality and favouritism within the camps. So not getting food rations because you’re not related to somebody or you don’t know the right people. In terms of safety I didn’t felt like they felt threatened within the camps.

Did you ever feel like you were in danger?

No not at all, you feel a feel anxious when you see lots of armed security and weapons around in general, but I wouldn’t say I felt in danger.

What’s it like seeing someone your own age in a refugee camp, with children they might not understand but seeing someone your own age, that could be you.

I think we really struggled with the fact that we met people that had to leave their home town and home cities and like within their second year of university or with only a few month left to finish their degree. And we thought, well, we have like less than a year to go and we’re complaining about finishing our assignments.

There’s a severe loss of hope with the people our age and nearly everyone we asked in the camp the question of going to Europe, the older generation and the younger ones said no, we don’t want to go we will stay here. But the people our age have a complete loss of hope in home, in Iraq, in the Middle East in general. They have no hope and just want to get out to Europe. And when I asked what’s in Europe for you? They said, we don’t even know, we just want out of here. They’re all qualified people, they’re not people coming here to scrounge off our benefits or whatever. They are all accountants, engineers, doctors, all these people stuck in camps.

When it came to the last few days we were shooting, we were sitting in the minibus and I said to Dylan, do you realise we’re flying out in 2 days? And we’re leaving these people and we don’t know what’s going to happen with them, we have no way of reaching them and finding out the future of their story unless we come back. And even then, we don’t know whether they’ll be here, back home, dead, or alive. In some cases if some of them made it alive to Europe then what?

Did you ever feel that the older people had already given up hope?

Everyone we spoke to said they wanted their children to go to Europe, they didn’t really care for themselves. With the younger children, the embargo was affecting teachers so the teachers are not getting paid in the camps. Its hard for the children, there’s a split between the ones who want to get an education and the ones who are angry about their situation and can’t focus.

Also what adds to the situation is [people’s] mental state: mental illnesses are not something that is addressed. These people have gone through a war in the past decade, they’ve gone through Saddam, they’ve gone through the Iranian war, they’ve gone through the war in 2003 and through all of [that] they’ve managed to stay in their homes and just live lives and carry on with in. And now after surviving two or three wars they’re just fed up, they have no idea what tomorrow is holding for them – it’s all unknown.

As an Iraqi person do you know enough of the politics to know whether there’s any sort of resolution, whether they’ll be able to go back? What thoughts did you come away with, despair or hope?

I think I’m still not settled on that, we’ve been editing it for two weeks and it’s still surreal to me that we were there and there’s so many different opinions. Even though there’s so much lack of hope, people get on with life. In the camps there’s weddings, there’s celebrations, even in those dark situations, people carry on day after day.

How do we talk about communities within the camp, just looking at the Syrian refugee camps, are there Kurdish refugees, Sunna, Alawite, do they live together, are they split?

One of the camps, there was Yazidis and Sunni Arabs, and there was a divide but no one ever said there was ever any conflict, they spoke different languages and they just kept to their sides. The vast majority of Iraqi displaced refugees that were there, Iraqi Sunnis, and they said the Shia generally wouldn’t come to these areas, they got to Karbala and Najaf and those Shia populated areas. But they had Sunni Iraqis, Kurds, Yazidis. The Syrian Arabs had their own sort of refugee camps, form what we were told there had been tension before they separated them but as soon as they had their own camps it was resolved.

Coming away from the situation having seen the impact of ISIS first hand, how did that impact your opinion on how we should tackle ISIS?

It’s not great is it, we’re going towards another war. I don’t think I have a solution to defeating ISIS. I’m from Mosul, the area they took over and one morning I was talking to my grandparents and everything was fine, the next day I find out they’re trying to get themselves smuggled out of Mosul to get somewhere safer. It happened so suddenly and they’re obviously very organised. What I heard from the people there, they said that their main financial resource is from selling petrol, but yeah honestly embargoes, no fly zones over Syria. Missiles, they don’t differentiate between militants, women or children.

How did you manage to make the people comfortable enough to open up about their experiences? Because in some of the interviews they spoke in a lot of depth and emotion.

Everyone was really open, they all wanted to get their story across. We told them that we want to show people in the West a different perception, and show that people want to understand their situation.

How easy was it to gain access to the camps with a camera crew?

I have family from Kurdistan that worked in the camps. My auntie worked in healthcare for women in one of the camps and my uncle was helping with distribution so we sort of gained access that way. We found someone who was the manager of the camps and met a lot of people, and a lot of people wanted the film to be made so gaining access wasn’t really an a problem.

Do you feel satisfied with what you got when you were there during the two weeks and do you plan on going back?

It was difficult when we were there. It wasn’t easy to get access to the camps. At some we only had a couple of hours because of issues with the management of the camps. But we were thinking of going back in the winter, we are satisfied but we know there’s a lot more to be shown that we couldn’t capture.

For the people that didn’t go to the refugee camps, what was your first reaction when your friends came back?

When we saw the footage it was really shocking and there are so many different stories that we didn’t expect to see. When we spoke to them when they were there we were asking about is it what you expected it to be like? And they were saying honestly there is no way you can prepare yourself for this. I think it really does come across in the interviews how desperate the situation is. We’re all mates round a computer looking at the footage and I just think wow this is actually happening. It’s amazing that these people can survive all that’s going on its incredible.

Crew members:

Elena Di Maria – Producer

Tom Sharp – Assistant Producer

Dastan Zorab – Director

Samir Haroon – Co- Director

Abdul Salih – Camera Operator

Dylan Zorab – Camera Operator

Dean Houghton – Editor

For further information on when ‘The Plight of Freedom’ will be released, please stay tuned at Huraia.