Twitter as a Voice for Indian Muslims

By Mohammad Ibrar, MA South Asian Area Studies

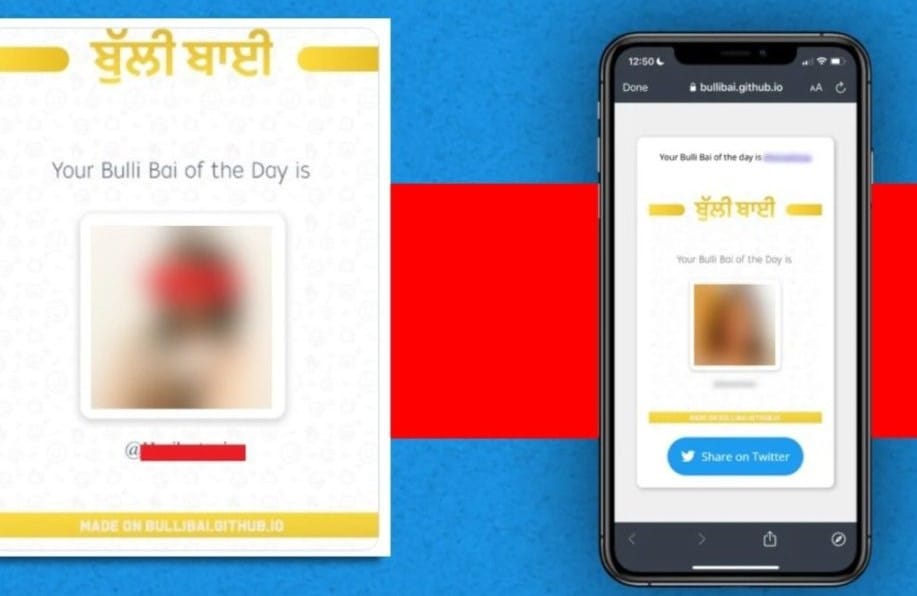

Several prominent Indian Muslim women woke up on New Year’s Day to see themselves ‘on sale,’ with their names and pictures being circulated with derogatory comments. An app called ‘Bulli Bai,’ developed by young Hindu men on the open-source platform ‘GitHub’ was the second such instance of anonymous social media users ‘auctioning’ Muslim women with such brazen impunity.

The first time was on 4 July 2021, with many women having their pictures used as part of the ‘deal of the day’ on a similar app called Sulli Deals. However, no arrests were made by the Delhi Police which is controlled by the Home Ministry of the Narendra Modi government and in charge of the investigation.

While the Sulli Deals app remained up for several weeks, the Bulli Bai app was taken down within 24 hours, with the Mumbai Police getting into action and arresting several suspects — all students in their early 20s — from multiple locations across the country.

Many of those arrested were found to be part of the ‘Trad ecosystem’ on social media — a group of young men and women who had based their ideology off of both Hindutva or political Hinduism, and from the alt-right movement sweeping in the West. These groups ran multiple Twitter handles and Instagram meme pages where they often used genocidal language against India’s Muslim community.

Amid the pernicious gloom of Indian social media and the incessant trolling, threats, and abuses faced by Muslim men and women on a daily basis, there is a sliver of hope.

For young Indian Muslims, Twitter and other platforms have become ‘a potent medium,’ says writer Hussain Haidry, a prominent voice of the community on Twitter who routinely questions and protests against hate speech by the so-called ‘fringe’ elements and by mainstream Indian TV media known for its daily hateful shows directed against Muslims.

The potency of the medium is clear from the fact that it was the relentless social media campaigns by young Muslims that bore result in the Bulli Bai app case. Not only was the case widely covered by the mainstream media after the near-silence in the Sulli Deals app case, but the arrests were quick and the usually silent political class came out acknowledging the bigotry and daily threat faced by Muslims, especially women.

As such, Twitter and other social media platforms have become the new protest ground for India’s Muslims whose physical assemblies always run the risk of being sabotaged by Hindutva followers to create street violence, which means more Muslims in jails. On social media, though still not a safe space to voice opinions, the fear of physical assault — by both police and others — becomes non-existent.

And so, hashtags are the new slogans and tweets are the new placards. Social media has given the voice to those desperate for a voice.

‘Given how craven the traditional, mainstream media is in India, social media platforms, especially Twitter, become an essential platform for Muslims to reclaim the narrative that has been spun about the community, and tell our own stories in our voice,’ says Fatima Khan, senior journalist at The Quint.

Continuously harassed for her reportage, Khan was among the Muslim women put ‘on sale’ in the mock auction on both the apps. She says the arrests were possible only because of the pressure exerted by Muslims on social media.

Khan is of the view that both street protests and online campaigning can and do co-exist. ‘As we saw during the anti-CAA movement (the nationwide protest by Muslims against the Modi government’s citizenship law that discriminates in granting citizenship from India’s neighbouring countries), Muslims were on the streets but also using social media to amplify their protests.’

Journalist Alishan Jafri is another prominent voice from the community who has been instrumental in forcing media spotlight on several cases of violence, hate speech, and crime against Muslims around the country. He says that Twitter and other platforms have helped Muslims to occupy spaces. ’Often liberals try to whitewash violence against Muslims. So, it becomes necessary for Muslims to take up space.’

He explained that in the past few years, many prominent Muslim handles on Twitter with a sizeable following have used hashtag campaigns to call for arrest of those who attack Muslims or have used genocidal language against them. And these campaigns have been successful too.

It was by the relentless pressure by Muslims that Hindu fundamentalist priest Yati Narsinghanand Saraswati, who routinely calls for Muslim genocide and exhorts Hindus to socially and economically boycott Muslims, was arrested — albeit for his derogatory comments against women.

In the Bulli Bai app case, it was Bombay-based Sidrah Patel who had filed a police complaint after her pictures were used on the app. She believes that the rot on social media is deeper than these incidents and Muslims have started to raise their voice on issues that were earlier never looked at or wilfully ignored.

“Muslims can use social media to not just call out epistemic violence but also change the discourse. The platform has helped level the playing field.”

She says that Twitter helps Muslims call out the hateful debates and incendiary depiction of Muslims on legacy media platforms. ‘During the early days of the Covid pandemic, The Hindu, a major national newspaper, published a cartoon depicting the virus carrying a Kalashnikov and wearing an attire generally associated with Muslims. I and many others called that out and the news organisation had to delete the cartoon and apologise. This shows that Muslims can use social media to not just call out epistemic violence but also change the discourse. The platform has helped level the playing field.’

This is what Jafri means when he says that Indian Muslims have used Twitter not to be in an echo chamber but to break the echo chambers that many progressives and liberals live in where they have certain presumptions about Indian society in general and Muslims in particular. ‘We try to break the dominant narrative on social media. Now, Muslims do the talking themselves and we do not rely on others to speak on our behalf.’

But beyond being just an open space for Muslims to voice their grievances and force administrative action, Twitter and other social media platforms have also emerged as a space for them to break stories, amplify opinions and publish reportage that mainstream media ignores. Opinions and editorials in legacy media platforms seldom invite Muslim scholars and authors for their views, even when the issues concern the Muslim community, such as the recent hijab controversy in the southern state of Karnataka.

Social media helps break the dominant narrative on the hijab issue, just as it does in platforming Muslim voices that would remain unheard. ‘Now Muslims openly call out their invisibilization, the whitewashing of crimes which were played down and even satire, which often punched down on them,’ Jafri says.

Khan, however, adds that the world is not as polarised as it is perceived and there are many ‘who are just understanding and learning and unlearning their politics… For them, social media plays a crucial role in expanding their worldview.’

Voices from India’s marginalised Muslims add to their worldview and present them with an opportunity to shed their inherent biases and engage with an open mind. The challenge is that an ecosystem is also at work alongside this and it wants to drown out the Muslim voice.

Photo Caption: A photo of the ‘Bulli Bai’ app (Credit: Ground Report).