What does the future look like for SOAS?

By Lulu Goad, BA Arabic

What does the future look like for SOAS? How does providing proof of bereavement for an extension support the well-being of the university community/student body? What kind of teaching do we want to experience at SOAS and how can knowledge be optimised in the space offered?

These questions formed part of the discussions that took place at a SU and UCU collaborative webinar on the 20 January 2022 titled, ‘Reflections on Bell Hooks: What kind of a University do we want to build together?’ hosted by SOAS academic Sophie Chasmas and SOAS SU Co-President (Equality and Liberation) Hisham Pryce-Parchment. A discussion influenced by the strikes at the end of 2021, it aimed to replicate the coming together of students and staff for a common goal, with the hope of continuing this narrative at SOAS in the future. Envisioning the ‘perfect’ classroom experience, the group was invited to comment upon what the challenges to achieving this were, how the university might go about tackling them and what role the union could play in this process. After an hour and forty-five minutes of conversation, and a few silences for contemplation, it appeared that perhaps a total reconstruction of teaching and learning was necessary to achieve what was collectively agreed to be the ‘ideal’ university.

The hosts opened the discussion by recalling the strikes from the previous term, recollecting the putting-up of gazebos, the fairy lights, the sharing of homemade food and drink, but most importantly the coming together of people in order to improve the working conditions of the university. Remembering this moment could easily have been disheartening, but, instead, the strikes were considered as a moment of possibility, driving us to consider what our university could be, beyond the confines of the institution as it exists in the present.

A quote from ‘Teaching to Transgress’ was shared in order to inspire discussion and with the strikes at the forefront of our minds many students and members of staff remarked on the importance of well-being in the university environment. Teachers shared their experiences as members of staff, with many commenting on the lack of consideration for their well-being and that of the students. Pryce-Parchment shared a particularly apt analogy which suggested that the classroom dynamic saw the student as consumer and teacher as authority figure or expert. With the student as consumer, it made sense to then consider the teacher as the product. Thinking about my own encounters with academic staff, whether over Zoom or in-person, the analogy feels very similar to the reality I have experienced during my time at SOAS. It is possible that students and teachers no longer exist as whole beings but just cogs in a system that continues to, as Hooks notes, ‘restore life to a corrupt and dying academy.’ Where is humanity in education? And how does providing proof of bereavement for an essay extension support the well-being of the university community?

“For the academic staff, it was suggested that vulnerability on their part would support a move towards a holistic model of empowered education. This would also require the abandoning of power dynamics, including dimensions of race, class and/or gender, entirely.”

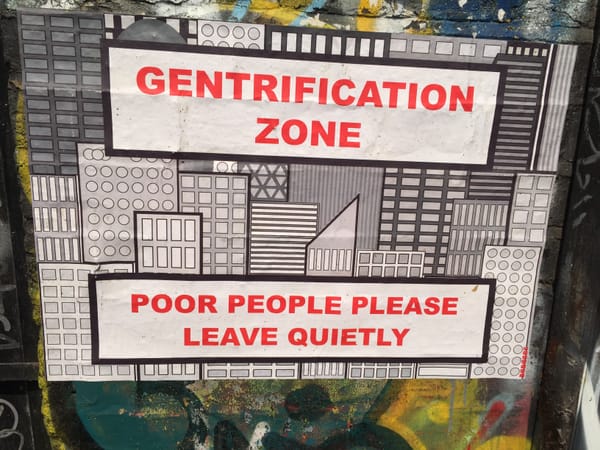

It also became clear that a shift in the student-teacher dynamic is necessary, turning instead to classroom conversation and interaction which is wholly reciprocal. For the academic staff, it was suggested that vulnerability on their part would support a move towards a holistic model of empowered education. This would also require the abandoning of power dynamics, including dimensions of race, class and/or gender, entirely. But how would that be possible within an institution which is considered to be founded on imperialism, imperialist ideologies and pedagogies grounded in whiteness? Throughout the discussion, Chasmas shared links to relevant talks and articles. One article in particular from the ‘Journal for Body and Gender Research’ considered how we should address traditional epistemologies in order to improve our education system. But it was the writer’s thoughts on how we engage with and challenge subject matter inherent to the institution of SOAS, were the most interesting. As a university that focuses hugely on the study of postcolonial and transnational theories, engaging with colonial structures within areas such as the ‘Middle East’ and ‘South Asia,’ the question was raised of how we, at SOAS, could displace Eurocentric ideologies in the classroom. It was suggested that in order to achieve appropriate teaching and learning on such subject matter would require the liberation from traditional means of the two by dismantling these pedagogies and re-building frameworks from scratch. It became apparent that if we were to continue as usual, centering whiteness and Eurocentric frames, that there was the question of what this learning environment was even for.

Leaving Zoom, I wondered how possible it really was to create the ‘perfect’ university, with so many issues to tackle. The conversation suggested to me that a whole re-evaluation of individual values was necessary, especially from those upholding the flawed ideologies that keep academic institutions afloat. Having been sitting in the National Theatre cafe I promptly left, heading home trying to think of where I’d last seen my self-help books.

Wrapping up, we were asked to recount anecdotes from a positive experience in the classroom at SOAS but as soon as the invitation had been given, those who had previously been avidly adding their thoughts to the conversion suddenly went silent. A few teachers chimed in to mention one or two encouraging stories from online lectures, but that was it. It seemed the classroom was even less inspiring than we’d all previously thought.