Dafydd Vaid, BA Linguistics & South Asian Studies (Hindi Pathway)

I’m on my year abroad in India, studying Hindi in Jaipur, Rajasthan. I just got back from visiting friends and family in Delhi, and I’m in a café, trying to write a Postcard to SOAS. But in my experience there are two SOASes, and I wonder which SOAS I’m writing to.

Am I writing to the SOAS that feels like a second home to people from various diasporas? I hope so. That’s the university where descendents of the colonised can study their ancestral languages, learn about the cultures they’ve been distanced from, and meet others with roots that span the world yet who share the peculiar pains and joys of being a person of colour displaced from their homeland.

Or am I writing to the SOAS for white students and staff? That’s the university where you can get a good degree in Arabic or Chinese for your finance or international relations career, or where you can learn an obscure and exotic language, culture, or instrument from another white person. It’s the school whose well-meaning students want to help the people of the third world through development initiatives and language documentation, rather than by prying the first-world corporate and governmental boots off of our collective necks. Maybe I’m writing to this one, the machine that assembles orientalists.

I suppose I’m writing to both. And as SOAS faces cuts and crises that are changing, even destroying, what many of us consider the core identity of the university, I worry that the SOAS I love will be abandoned in favour of a whiter, less radical SOAS. That would, I suppose, be a return to its roots.

‘…I worry that the SOAS I love will be abandoned in favour of a whiter, less radical SOAS.’

SOAS has a foul origin. It was created to train agents of the British Empire, instructing them in the languages and cultures of conquered peoples in order to optimise their subjugation. It was founded only months after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919, in which British soldiers trapped peacefully assembling civilians in a walled public garden in Amritsar, Punjab, and opened fire on them, maiming and murdering over a thousand people. It was founded to serve and further that exact agenda of violence and domination. And when I think about SOAS, and about returning next autumn, I wonder if its work has fundamentally changed. Now as always, it teaches and sends out into the world throngs of white Westerners, empowered and emboldened by their blurry understanding of the people upon whom they will build their careers.

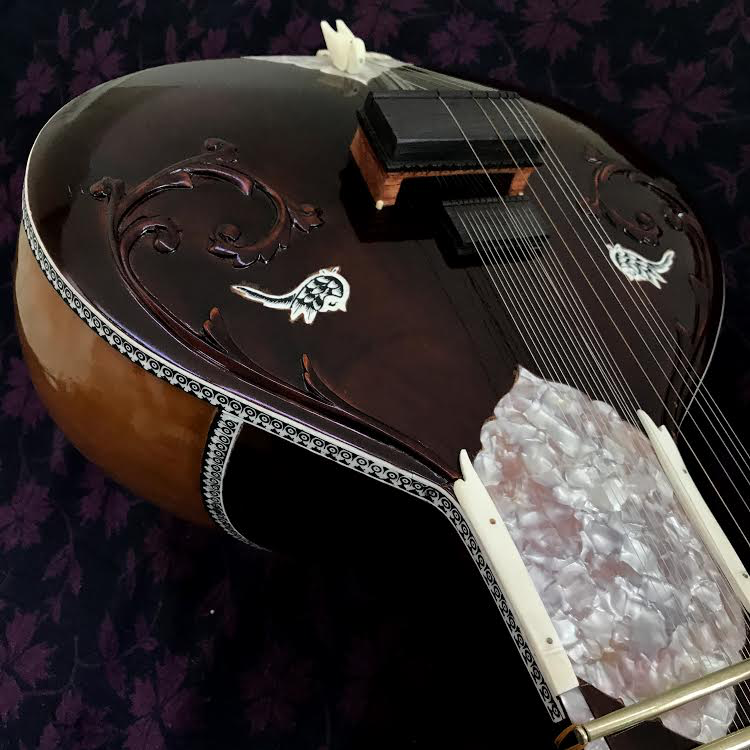

I don’t mean only to trash SOAS. Although it’s where Enoch Powell learned Urdu, it was also a means for Paul Robeson to connect with Africa. It’s how I’m here in my homeland right now, rapidly improving in Hindi, visiting my Indian family for the first time in ten years. I’m even getting to study sitar, which is changing both my understanding of music, and my approach to writing it. I’m having the time of my life, but I’m also looking forward to returning.

SOAS, I hope you continue to reject your roots while I’m away, once I return, and long after I graduate.