Ciels Liquides (1990) By Anne F. Garréta

Jack Samuel Griffin, MA Middle Eastern Studies

Translator’s Note

Liquid Skies is initially a story about a family, tracing its genealogy from rural French bourgeoisie to cosmopolitan Parisian intelligentsia. Our protagonist is the embodied representation of this displacement: throughout their adolescence, they were sent abroad by their parents to master numerous foreign languages while the neglected family farmhouse rusted and weathered.

This social and spatial upheaval, so typical of the autofiction style that oulipienne Anne F. Garréta has kept at arm’s distance, is only the beginning of a much wider tale of disintegration. When the protagonist suddenly loses all language, the world they inhabit takes on a haunting fluidity. They float with alarming indifference through different locations and arrangements. They lose all solid ground.

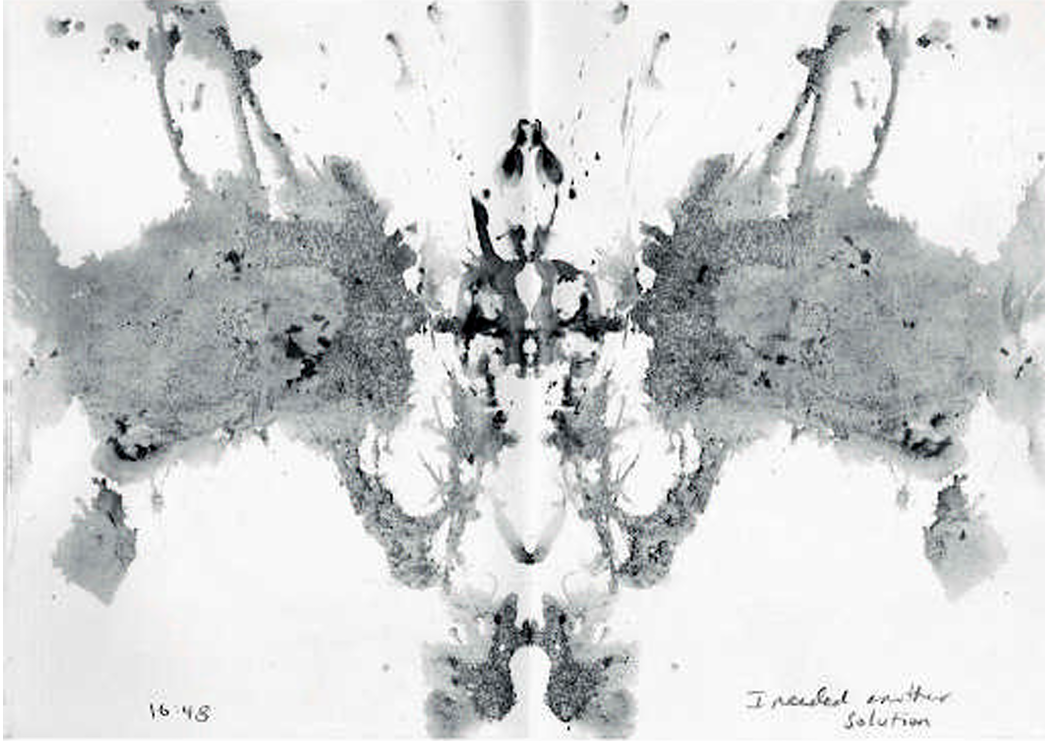

Liquid Skies is, in its themes, an evidently twentieth-century tale. The sudden disappearance of language coincides with the decay of all order, a particularly Dadaist and Surrealist preoccupation, one also hinted at by Foucault in his mention of aphasics in the preface to The Order of Things. But it is unclear, without language, upon which arena this theatre plays out, thereby illustrating the contingency of the notion of a subject distinct from the world. Through its illustration of the slippages and gaps of meaning in language, the text actually interrogates the subject as interpellated by language. With the protagonist unable to access any referents, the structure of order, which is supposed to be surveyable from above, dissolves so immediately that it becomes totally uncertain if it is the world or their subjectivity (or both) that is being inked out.

If Garréta’s intention is to undermine the concrete certainty of the distinct subject, then she insists just as much on the materiality of the spectral. Lurking at the margins, the farmhouse haunts every page, and is the place of return for the troubled protagonist. You would be forgiven for forgetting about the family by the end of the text—but you will not have forgotten about the unrelenting physicality of the farmhouse, which, although dilapidated, remains in the fear-struck and isolated oasis of wordless dream.

I encountered a number of challenges translating the extract, of which I will mention only one. In Chapter 10, Garréta was able to perform a double entendre that seemed, to me, to contain all of the novel’s tension: ‘mais sur le papier devant mes yeux, bâtons, points, serpentins, un monde de vers grouillait’ [‘but on the paper before my eyes, sticks, points, squiggles, a world of verse/ worms wriggled’].The French ‘vers’ can mean both ‘worms’ and ‘verse’, and so the ‘world’, the newspaper page, may represent positive text but also the crawling worms symptomatic of this text’s limit, failure, and death. I am indebted to Emirhan for drawing my attention to ‘(de)composition’, a version of which I went with. Many of my friends kindly thought on this conundrum with me, and I invite you to join–I would be thrilled to hear your renditions.

Translation

8- One fine autumn day I realised that words were escaping me. I found myself on multiple occasions utterly incapable to label or designate an object before me. In every language that I knew, it had lost its name. I managed for some time to hide this persistent handicap of which I was more ashamed than afraid. I would sense a sudden shadowy void, an inkstain emerge and encroach before the black tide pulled out and swallowed all my terms in a wave of night, forcing me to cut short whatever conversation I was in or phrase I had begun. I coped temporarily. Anticipating the obscure lament I would mirror my interlocutor, quickly repeating the last words they used before they too were taken by dark waters. As for the written word, I could merely let three droplets of the very ink flooding my head drip onto the page. I reassured myself once the flare-ups had passed that too little sleep and too much schnapps, work, coffee, and jet lag had momentarily upset the delicate Austro-Hungarian empire in my head. I stopped drinking coffee, replacing it with lime blossom tea or milk sweetened with honey. I gave up schnapps and so insomnia returned, leaving me alert in the night. Totally powerless to fight the tide, I felt myself drift away. The washed-up barn, silent and monumental, still stranded in the depths of the abyss, beckoned to me, opened its two immense doors, there, at the end of the vibrating spiral of my waking dream, and the mechanical lift, four months abandoned, was stood waiting for me, intact.

9- 9 I woke up one morning with my throat contracted. As usual, I was alone. My apartment, a small dwelling beneath the building’s roof, was not far from my university. I took my morning shower and warmed some milk in a saucepan on the electric stove for my breakfast. The snare at my throat seemed to release a little with the honey. I endeavoured, through the regularity of my morning routine, to banish the anxiety that I sensed glimpsing through. In front of the building the concierge was propping up the bins that had fallen over. Her mouth opened and contorted abruptly. I waited for her speech to reach me, but its sound was fuzzy, faint, and muted. I pulled the door to a close and hurried furtively down the boulevard. A tidal wave crashed upon the shore of my mind. I coughed twice as I walked, attempting in vain to scrape up a few phonemes. Feeling my face redden, I lowered my head, completely helpless to identify whatever condition had taken hold of me. I could do nothing, only wordlessly apprehend my throat’s contraction and the dark and muddy tide flooding my brain. I fixed my gaze on something, I don’t remember what, that was moving rhythmically on the ground. It was certainly there, I was well aware of its cadence. Something behind my head–I could have touched the exact point, the place of this awareness–recognised it, knew where it was positioned in space and that it belonged to me. But no name, nom, wort, volunteered itself to this awareness so calm and so certain. The words, like petrified larvae in their shadowy corner, enclosed in the night…

10- 10 Only muscle memory guided me. I recognised the wrought iron gates of my university. The same automation led me, like every morning, to the library where I would read various foreign newspapers. A light panic stabbed at my heart. But I was strangely assured that, as they had done before, so too this flare-up would pass. I found myself sitting in the same armchair in front of the same window that gave onto the same courtyard. The surrounding objects, their intelligible forms and neatly contoured shapes, were totally familiar and banal; I recognised them, namelessly, as identical to themselves. Yet I couldn’t begin to decipher the newspaper. Lines, dots, strokes: a decomposing composition was writhing before my eyes. In one night, I had lost the fruits of twenty years of learning. Every language, including my mother tongue, had become completely and utterly foreign to me. Lunchtime. Back at my apartment as usual, I tried to sleep, lying in bed with the shutters closed desperately believing that if I could only have a moment’s oblivion then perhaps my brain’s previous order, undone in one dissolving night, might be restored. I hoped that, upon waking up, the world’s signs, revived, would reclaim their shape and meaning. Words had abandoned me, but in their wake remained their possibility, their mould, their empty chrysalis. With sleep refusing to come, I instead set to locate the point of catastrophe in my brain, where frozen signs and drowned words were waiting, veiled beneath black ink. Calling upon them as talismans, I had soon strewn upon my bed the largest volumes I could find in my book collection. I waited for these cinderblocks of fragile word to bring forth the shadow lurking in an out of reach fold in my memory. The hunt was on. I turned on the radio and flicked through every station. Voices, their melodious vibrations, reached me before losing force and dying at the threshold of meaning. Nightfall. I ran my fingers through my hair and caressed my skull, feeling at the surface of the boned cage for a protrusion, soreness, or any other proof of the subjacent disaster lying beneath. There, I noticed for the first time a number of hills and valleys. I imagined the surface cleared in order to map it out, and plotted a series of points in my mind. The telephone rang, and then fell silent. Immobile in my bed, I tried to return to the soft light of the old barn by the cliff face. But the strand was lost, tangled and knotted around my throat, and the nocturnal spiral dismembered.