Alice in London

Alice in Wonderland is showing at the British Library until Sun 17 April 2016 and is free.

Kay Lee, LLB Law

I stumbled upon the exhibition almost as curiously as Alice stumbled down the rabbit hole – a little dazed and confused – but unlike poor Alice, I ended up pleasantly surprised. To celebrate 150 years of Lewis Carroll’s fantasy dream, this exhibition explores how Alice captured generations of wonder through a journey consisting of Carroll’s original manuscripts, illustrations and interpretations over the years.

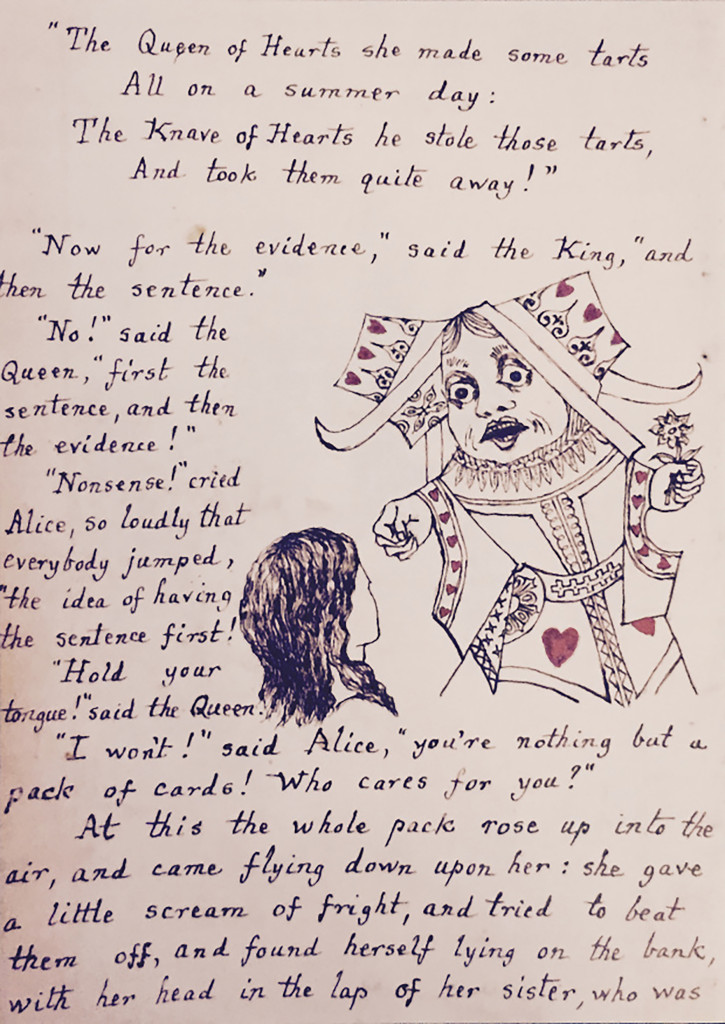

Life-sized illustrations of bottles and the Red Queen welcome the visitor as they enter. The main area is separated into three parts: the story Carroll told Alice Liddell, the publication of the original text, and the memorabilia and spin-offs it has spawned over the last 150 years. The highlight is undoubtedly Carroll’s original manuscript, upon which he scribbled and fleshed out the inspiration for his story.

I also enjoyed studying the interpretations and re-interpretations of the Alice story over the decades. The famed artist Salvador Dali’s depiction of Alice was also on display, suggesting how Alice’s enchanting story has touched all of us over the world. It was interesting to note that no matter what the interpretation of the story was, and regardless of who was interpreting it, the story never strayed far from Carroll’s original.

The pop-up shop for the exhibition is littered with all sorts of items, from dainty plates and journals written in pretty script to colouring books, all of which tempt both adults and children alike. While the exhibition is not as large or grand as one might expect, the pop-up shop offers visitors a place where they can browse and purchase the parts of the Alice story that resonate the most with them.

Alice in Wonderland’s marketing heyday seems endless. Even today, every variation of the Alice story has been done to death. From Tim Burton’s creepy live-action film rendition to Electronic Arts’ psychological game thriller versions and Disney’s lovable, children’s cartoon, Alice continues to inspire. The underlying and overlapping themes and layers to the Alice story will continue to be unwrapped and unravelled, as we interpret her story in new lights and new perspectives.

Like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, our adventures through this strange and sometimes twisted and confusing world will scare us and cause us to question our decisions. Like Alice, the world will continue to try talking sense and convince us with reason in an otherwise senseless situation. But like the Cheshire Cat says, “Imagination is the only weapon in the war against reality” and the continuous wonderment Alice gives us is a reminder of that.

Facing or Fetishising the Imperial Past?

‘Artist and Empire: Facing Britain’s Imperial Past’ is showing at the Tate Britain. It’s an expensive exhibit at just under £13 for students. If you still want to go, it’s on until April 10th 2016.

Annemari de Silva, MA South Asian Area Studies

Firstly, ‘past’ is a misnomer, no? The tactical use of ‘Britain’ and not the ‘UK’ hides the fact that the empire still continues in Northern Ireland. Interestingly enough, to align with this historiography, there are no examples of any aspects of empire in Ireland in the exhibit.

So does the exhibit do what it claims to? To ‘Face’ Britain’s colonial past? Of course not, even though other popular reviews in the media call it daring and blunt and other words associated with bravery. The exhibit is a mostly chronological narrative of Empire across the world, (except for contemporary UK, as mentioned), told through portraits, sculptures, crafts, maps, paintings and other visual art.

As one of the people with whom I went stated, this exhibition could essentially be yet another Victorian World Fair, simply transplanted in time. It isn’t particularly nostalgic or proud but is entirely from a British perspective that whitewashes the horrors of colonialism as experienced by the colonised and over-sympathises the British losses in the colonies. Moreover, the narrative of ‘discovery’ that defines the first two large rooms is trite, old, and not constructive in forming even a smidgeon of nuance in the British public’s understanding of Empire.

For me, as an outsider, it was interesting seeing the British perspective of colonisation. Not that I empathised with it but it was useful to understand how propaganda worked and to see the material culture and categorisation that shaped ‘knowledge’ as we experience it post-colonisation. However, what is abhorrent about this exhibition is that it puts the onus of understanding Empire on the observer.

There is no explanation of colonial practices, none of the brutality, nor any mention of the detrimental consequences that colonial categorisation had on world knowledge. The discovery rooms – with their maps, tribal artefacts, categories of people, classifications of animals and plants (named of course after colonial botanists and zoologists) – do not refer explicitly to the fundamental manner in which European physical and social science completely altered global knowledge. It is such a wasted opportunity because there are so many incredible artefacts on display, so many opportunities to discuss even vaguely (or bluntly) the relations of colonisation with contemporary skewed global knowledge.

My other discontent was the absence of artist in this exhibit. Apart from brief mentions regarding singular works, this exhibit really was more a documentation of Empire rather than an exhibit dealing with ‘art’ in any useful or comprehensive sense of the word. An anthropologist would gain more out of this than an art historian.

On the relative upside though were the final two small rooms that displayed dissident artwork by some postcolonial intellectuals. As an Australian, I was surprised and very excited to see the work of important Aboriginal artists, (who still find it absurdly difficult to gain space in public institutions in Australia), amidst other renowned and comfortable figures of Australian art such as Sidney Nolan.

However the intellectuals taken from other cultures seem to be part of the nationalist elites that completed the classic narrative of journeying to the colonial centre and returning to their homelands to be in touch with the people. Some of the artists were truly revolutionary in terms of a European (and arguably postcolonial) art narrative but these intellectuals’ version of dissidence is the type that still sits well with the status quo.

So really, there was nothing about this exhibition that warranted the tagline ‘Facing Britain’s colonial past’ nor the inclusion of ‘Artist’ in the headline. ‘The World Fair: 2016’ would have been far more fitting.

Museum of Innocence

Somerset House’s ‘Museum of Innocence’ exhibition is on until the 3rd April.

Mel Plant, BA Arabic and Turkish

Somerset House’s ‘Museum of Innocence’ exhibition is a must see for anyone who has read an Orhan Pamuk novel, aspires to be a writer or has visited Istanbul. I lived in Istanbul over this past summer, in the spirited, crumbling, historic migrant neighbourhood of Tarlabasi.

The exhibition consists of 13 ‘vitrines’ (glass cabinets filled with objects) brought over from the Museum of Innocence in Istanbul, as well as short clips taken from the film ‘Innocence of Memories.’ The film, based around Pamuk’s novel ‘Museum of Innocence’ and his memoir ‘Istanbul,’ contains ghostly walks which float us through the abandoned streets of Istanbul at night. These film clips, and the various objects which fill up the museum’s ‘vitrines,’ put me in an extended state of nostalgia for the city I love and have loved in.

The ‘vitrines’ are collections of objects collected by the main character of the novel, Kemal, and invoke the same sense of bittersweet, unrequited love that both the novel and the city exude. I’d recommend that you read the Pamuk’s ‘Museum of Innocence’ before visiting the exhibition, which finishes on the 3rd April.

However, for any aspiring writer, the display of Pamuk’s colourful manuscripts, peppered with sketches, is highly insightful. To witness the creative process of one of my favourite authors, amongst objects showing the story this process created, was beautiful. So, take a 15-20 minute walk from Russell Square to Somerset House (next to the Kings’ Strand campus), and spend your break amongst these enchanted objects imbued with the innocence of memories.