Ex-Guantanamo Detainee Blasts Government Prevent Strategy

Sophie Bush, MSc Development Studies

Former Guantanamo detainee Moazzam Begg has condemned the government’s ‘anti-terror’ strategy, labelling it a ‘toxic brand.’ He was speaking to students and members of the public at an event held at UCL and coordinated by SOAS’ Decolonising Our Minds society.

The controversial strategy, called Prevent, aims to tackle extremism in Britain by forcing institutions and affiliates, including after-school clubs, to share information with the government. The SOAS Students’ Union has already described it as ‘Islamophobic’ and has refused to comply with a Prevent ‘working group’ set up by University administration.

Last year, 12,000 people were referred to the programme, including many under 18s, some of whom were interviewed by police and Prevent teams without their parents or other advocates being present.

‘This policy is not only pre-crime, it’s nonsense,’ said Begg, who is the outreach director for CAGE, an organisation that helps communities affected by the war on terror. It is a subject he knows too well, having been arrested, detained, tortured, and interrogated – most recently in 2014 – without ever being charged. He added: ‘We are subject to the whims of British government. Terrorism is a non-white concept as perceived and legislated for by government.’

Also speaking on the panel was NUS Black Students’ Officer Malia Bouattia who blasted the amended legislation affecting universities and other institutions as a ‘desperate attempt’ to save the Prevent programme, which has been policy since 2006. ‘Prevent has created a matrix of surveillance,’ Bouattia said. There is ‘no time for appeasement – only full opposition. NUS has tried to be in rooms with people and deal with this but it is rolling on and out.’ The NUS are running nationwide ‘Students Not Suspects’ events that highlight the lack of a causal relationship between universities and extremist views, despite David Cameron having urged the NUS to stop its opposition to the government’s strategy.

Critics, including the Preventing Prevent panel, deem the strategy a ‘pre-criminal space’ that alleges to protect as yet undefined ‘British values.’ Research has shown that extremist ideas don’t lead to acts of terrorism, and that any opposition to the state could in fact constitute extremism.

Hilary Aked, a researcher involved with the Spinwatch initiative run at Bath University, said ‘think tanks and other agents that helped prep for Prevent – including the neo-conservative Quilliam Foundation – legitimise this kind of governmental policy and behaviour. An article published on September 30 demonstrates a statement lifted word for word from a far-right think-tank.’ The Quilliam Foundation, which has received thousands of pounds in government funding, promotes itself as a ‘centre for social cohesion,’ but is widely criticised and has been absorbed by the Henry Jackson Society which ‘serves as a bastion of trans-Atlantic neoconservatism,’ according to the Institute for Policy Studies. ‘Government policy has created a cottage industry of experts,’ such as Quilliam, stated Aked.

Communities from North Africa have been identified by councils as being of particular interest to the Prevent programme. Well over 12,000 of Britain’s 86,000 prisoners are Muslim, despite the group comprising only 5% of the national population. Prisoner numbers nationally have risen by 20% since 2002, but this increase in the jail population has been vastly outstripped by the rise in Muslim inmates – up 122% in the same period.

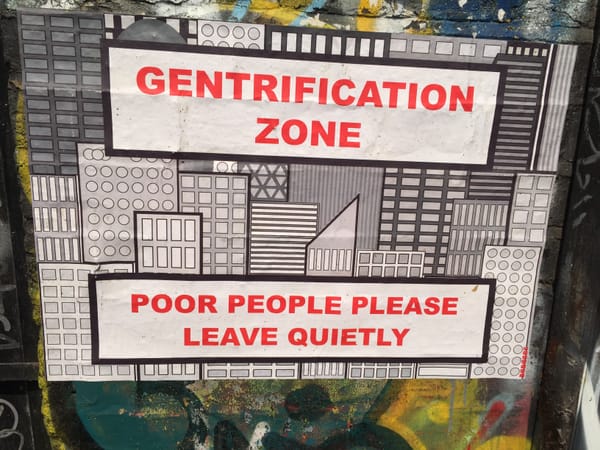

Along with targeting minority communities, policies such as Prevent are said to contribute to a sense that our society lacks spaces without government surveillance in a culture permeated by fear and censorship – such as universities.

CAGE has welcomed the NUS’ ‘principled opposition’ on Prevent and the government’s Counter Terrorism and Security Act, stating ‘a growing number of trade and profession unions have expressed concerns about being required to act as agents of the state.’

Universities have been asked to report on students ‘at risk of extremism.’ One SOAS tutor, whose name will not be given, said they would not ‘inform’ on any student or actively implement Prevent. It is not known how many tutors are dissenting, and what, if any, disciplinary measures could be taken against those demonstrating similar, critical behaviour.

The attempts of Prevent to dismantle the culture of tolerance and free speech on campus is particularly poignant given the appointment of Valerie Amos, who has not yet issued a statement regarding such policies being forced onto campus or their enforcement by School administration.

Prevent, and other policies like it, raise the question: does this kind of legislation lead to further animosity, bearing in mind the popular view that much extremism exists as a result of Western foreign policy? Begg made his position of informed, critical resistance clear: ‘We know you’re watching us. Well, we’re watching you right back.’