The Fight for Minority Languages, in SOAS and Beyond

Anonymous

On the 9th of December 2024, the 20th Central Committee Politburo of the CCP held its 18th collective study session, presided over by Xi Jinping. During this meeting, XI reiterated his vision for an ethnically harmonious state. Stating that his party has to focus on “continu[ing] to deepen efforts on ethnic unity and progress, actively build an integrated social structure and community environment, and promote the unity of all ethnic groups – like pomegranate seeds tightly held together”.

The People’s Republic of China officially recognizes 55 ethnic minorities alongside the Han majority. According to the National Bureau of Statistics’ 2020 census, ethnic minorities make up 8.89% of the country’s total population. However, the assimilation of ethnic groups into a Han-dominated society has been a key feature of Xi’s premiership, and the reports of the December study session represent another nail in the coffin of Chinese ethnic minority rights. Particularly pertinent in the reports was Xi’s reiteration, that Mandarin should be “spoken more broadly” in the frontier regions in order to “continuously enhance their recognition of the Chinese nation, Chinese Culture, and the Communist Party.” Although freedom of minority languages is theoretically protected under Article 4 in the PRC constitution, control of language education, in the eyes of Xi- remains an essential part of national security, as promoting ethnic languages could foster nationalism and separatism. In China teaching minority languages is strictly controlled by the Bureau of Education, particularly in sensitive areas such as Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong.

Now, more than ever, SOAS should be investing and widening its language offer ings. Languages are touted as being the bedrock of SOAS’s academic mission; evident via SOAS’s 2016-2020 ‘Vision and Strategy’ documents, which make constant reference to the fact that our institutions key pull factor is our diverse language offerings. In reality, language offerings have never been in a more precarious position. Within the context of Chinese ethnic minority language offerings, SOAS has dropped 2 previously offered modules: Hokkien and Modern Tibetan, and attempted to covertly drop Cantonese until it was brought back- due to popular student demand. Southeast Asian language programmes have also bore the brunt of reforms, with whole degree programmes in Thai and Vietnamese dropped in recent years. Where SOAS on paper stands as an institution that should be a bastion of language protection and preservation in the face of chauvinists like Xi Jinping, the reality of the course plotted by the Board of Directors is much more in line.

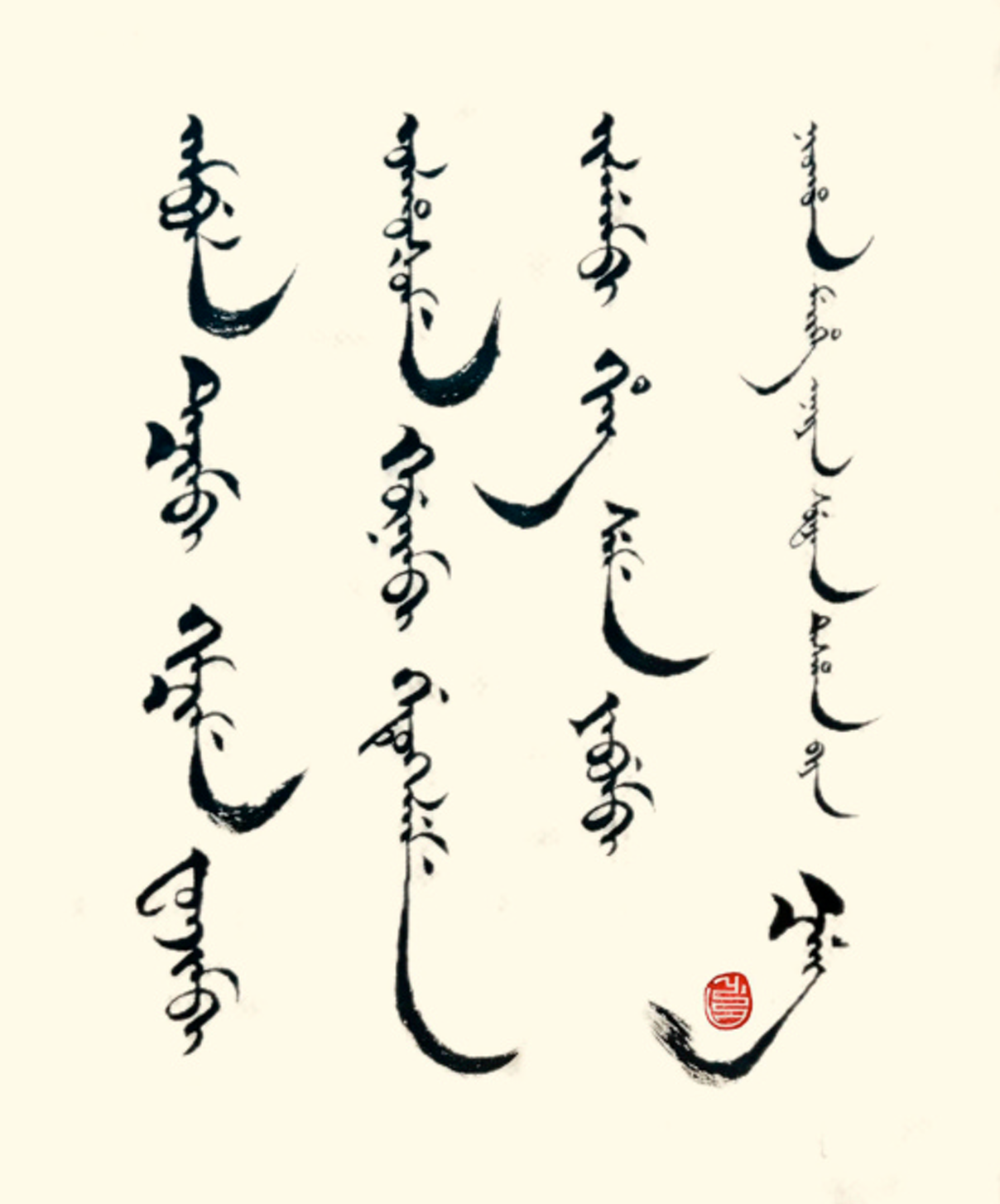

The future is not all dark, however. The School of Languages, Cultures, and Linguistics is working on proposals to increase its African language offerings, and continuous attempts are being made by the Manchu Society and the Mongolian Society respectively to provide extra-curricular language offerings, amongst many other examples of grassroot organising.

What is needed is two fold: pressure on management to support language offerings, and student support for minority languages in the form of module enrolment. With this in mind, I urge students to think about taking language options in the next round of module selection.