Ella Linskens, BA Arabic

This was my first time in the Bertha Doc House since the Curzon Bloomsbury opened in the Brunswick. If you’ve been to any Curzon around London, you’ll recognize the stylish interior and the combined bar and ticket desk. What is unique about this Curzon is that it is home to the Bertha Doc House, a cinema dedicated solely to documentary screenings and events.

I was there to watch the premiere screening of Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, which was followed by a Q&A session with the director, Stanley Nelson, and Mohammed Mubarak, an ex-Black Panther Party (BPP) member who was featured in the film.

The movie begins with interview footage from ex-BPP members, but you only fully realize the revolutionary spectacle you’re about to witness when the song Power to the People comes on.

The movie approaches the Black Panther issue chronologically, and the interview and real life footage is punctuated by key dates. This timeline starts in Oakland in 1966 with Huey Newton’s revolutionary move to fight police brutality by taking advantage of the right to bear arms.

The film gave me an incredible sense of the energy and overwhelming momentum that the movement had at the time, and what it must have been like to witness it as an everyday phenomenon.

As the movie continues, our sense of the movement widens and deepens. We hear it described as bold and courageous. We hear an ex-member describe the BPP as having “swag,” and how although “Black is Beautiful” wasn’t a new idea, the Black Panthers showed that urban Black is beautiful.

We see the implementation of survival programs, such as serving breakfast in the staggering scale of 20,000 meals a week to 19 communities.

We meet FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who considered the BPP to be the biggest threat to the internal security of the United States, as he begins a counter intelligence program to neutralize black nationalism.

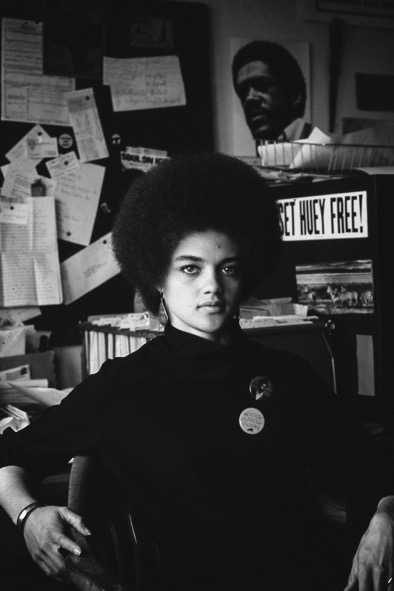

We see elements that are often forgotten in the classical images ascribed to the BPP, like the huge role that women played in the movement. Although the BPP wasn’t free of chauvinist tones, they went a long way in changing stereotypes – women had guns and men cooked breakfast. My favorite line from the movie, and perhaps one some female activists can relate to today, is, “We didn’t get those brothers from revolutionary heaven.”

Stanley Nelson said it was a purposeful effort of his to correct things that had been misremembered such as how young BBP members were, the role of women, and how they formed mass and far-reaching coalitions. Nelson expertly weaves together media reports of the BPP, testimony from its members, and beautiful stills and documentary footage from the time, to portray the complexities of the movement and its importance as a cautionary tale.

When I pried my eyes away from the screen, I saw that everyone in the audience was transfixed by the story being told; some were even on the edge of their seat. And this was my experience as well.

The movie had me experiencing both extreme beauty and extreme dread, sometimes simultaneously. As the rhetoric of the BPP escalated and the movement began to destruct, we are reminded of an undying sentiment: “What remains true? An undying love for the people.”

The movie is perhaps particularly relevant today when one considers the ongoing police brutality against minority youth, an issue Nelson describes as “more up front than it’s ever been in the history of the United States.” The film manages to capture the spirit of revolutionary fervor, and that is why it is definitely worth watching.

All Photos stills from the Movie