Chagos Islands: The Battle for Sovereignty ensues

For over half a century, the United Kingdom and Mauritius have heatedly debated the sovereignty of the Chagos Islands. Located in the Indian Ocean, about 500 kilometres south of Maldives, the Islands have been subject to severe encroachments on their sovereignty since 1965, when the UK and Mauritius made a provisional agreement confirming the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago. The UK made this decision under pressure from the Kennedy administration, which wanted to host a US military base on the Islands. The US was particularly interested in the largest island, Diego Garcia, which now hosts nearly 4,000 military troops.

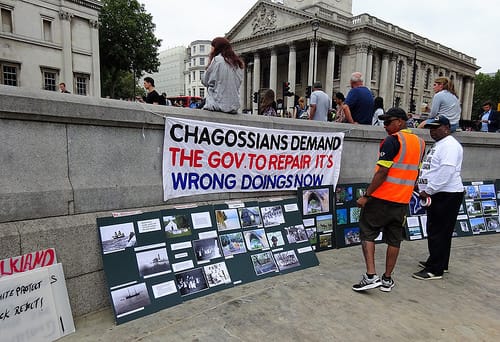

However, in 2018, Chagossians continue to fight for their autonomy before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), refuting the UK’s claims to their land. In early September, the ICJ dealt with the ‘Legal consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965’ case. The UN General Assembly brought the case before the ICJ, as an appeal for an advisory opinion on the legal status of the Islands. The dispute arises from the UK’s decision in April 2010 to create a Marine Protected Area (MPA), currently the world’s largest, around the Islands.

The UK’s official stance is that it legally gained regional sovereignty as far back as 1814, and therefore indisputably holds ownership of the region. The British solicitor general, Robert Buckland, admitted that the forced removal of the Chagossian people was ‘shameful and wrong’, adding that this sovereignty debate is ‘purely bilateral’, pushing the ICJ not to take the case further. By contrast, Mauritius argues that the UK’s establishment of the MPA breaches the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (UNCLOS), and further argues that the Islands are still remnants of British colonies.

The British-Chagossian community is deeply feeling the consequences of this scenario, which former Mauritian president Anerood Jugnath coins as ‘incomplete decolonisation’.

Between 1967 and 1973, approximately 1,500 islanders were made by the British government to leave their homes to make space for the American military base. Although the islanders have since consistently fought for their right to return home, in 2016, the UK extended the USA’s ability to use the Island until 2036, further barring the expelled locals from a return.

This situation has most affected the third-generation of Chagossian migrants. A Home Office spokesman explained that ‘under British nationality law, citizenship is only passed on to one generation abroad. This means that the grandchildren of the resettled Chagossians do not have a claim to British citizenship’. For example, Jeanette Valentin, who lives in Milton Keynes, has two daughters whom the government may deport unless she can raise £8000 for their citizenship, a privilege they were not entitled to at birth, as they are third-generation UK-based Chagossians. Valentin’s mother herself was deported from Diego Garcia by the British government in 1971, exiled to Seychelles, without having received any compensation or support from either state for her livelihood. Valentin says, ‘[The UK government] removed my family [from the Chagos Islands] and put a military base, but now don’t want my kids to be British citizens’.

The Chagossians are now starting to receive partial support, particularly from Conservative MP Henry Smith, who has put forward a private member’s bill, the Crawley British Indian Ocean Territory (Citizenship) Bill, to provide a method for all those of Chagossian descent to be able to lay claim to British citizenship. This has been met with an encouraging response as it received backing from the House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee, and it is now being processed for its second reading at the Commons. Smith raised the concern that ‘the threat of deportation is hanging over young people just leaving school whose parents are British citizens’.

The ICJ judges have not specified when they will release their advisory opinion. Although it will not be legally binding, it will still carry great significance in the realm of international law.

Noor Mandviwalla, LLB Law Single Honours