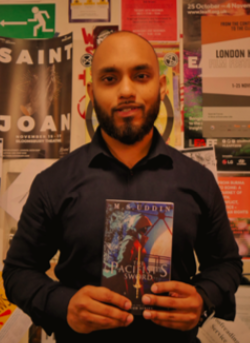

HUMANS OF SOAS: Saif the Writer

Interviewed by Uswa Ahmed, BA World Philosophies

The SOAS Spirit sat down with the author of “The Pacifist’s Sword” and SOAS Alumni “Saif the Writer” to talk about the difficulties of pursuing a career in writing.

Uswa Ahmed: Introduce yourself?

Saif: My name is Saif. I am a former SOAS student and author of “The Pacifist’s Sword”.

UA: When were you at SOAS and how has your time here influenced your writing?

S: I came to SOAS in 2013 to read History and Study of Religions. I’d say that my time at SOAS has been a hugely influential factor in my writing.

SOAS always brought a very different approach to pretty much all the core beliefs I held dear and forced me to challenge my perceptions. In doing so it brought me face to face with alternative perspectives that I would have otherwise overlooked or dismissed. Now as a history teacher, I bring in a lot of what I learnt about the problematic complexities of world history into my lessons.

UA: In the book, everyone prescribes to the religion of “WIFIism”. How did that come about?

S: Part of my joint honours was the Study of Religions and I feel that it hugely informed how I went on to construct the idea of religion in the book. I was thinking about how dependent we are on the internet today and felt it was an important metaphor not just for our relationship to the internet but also how our obsession with it is almost religious.

UA: The book is set in a dystopian Whitechapel. What was it like growing up in London and how has that informed your writing?

S: I was born in Newham and we lived in the part of Stratford that went on to be renovated and demolished for the 2012 London Olympics. I myself was displaced by the council and moved elsewhere in London. At the time I was around 11/12 years old watching this wave of gentrification take over my community. I myself have witnessed a lot of change in our city.

UA: What challenges have you faced as a minority pursuing a career in writing?

S: I come from a traditional immigrant household and as you can imagine, the importance of attaining a good education is drilled into us from a very early age. I picked up by 12/13 years of age that I was really into poetry and art.

What I picked up on at 12/13 years of age was that I was big into poetry, rap and those kinds of art forms. But what I quickly recognised was that coming from an Asian background you can’t exactly go into music or writing because of the way in which these types of careers are stigmatised in our communities. I mean how do you even have that conversation with your Asian parents who want you to become a doctor or engineer. It’s then even more difficult to initiate a dialogue about these kinds of things with family. I remember thinking to myself that I know I’m good at putting words together, but I also had to think about what was considered a “respectable” profession, one that my parents would support me in. A lot of my friends have that urge to go into alternative career paths but they feel as though they can’t do so because it’s such a taboo to even contemplate the possibility and with that, their dream dies. But then I decided that I wanted to use my passion and just begin writing something, which eventually led to this book.

UA: Do you feel as though you have a responsibility towards the young people of this city who grew up in similar circumstances to yourself to pursue their passions and in that sense be a role model in your community?

S: I initially did struggle as most first-time writers do. I got so caught up in the process of getting published that it drowned me in self-doubt. This is problematic on a number of levels because it has the effect of killing the art before it gets a chance to be out there. After my book came out I saw all these young people were starting to look up to me which was flattering but I somehow didn’t feel as though I was worthy of that praise. But I feel as the imposter syndrome wears off, I realise that I want to hold the torch for British born Bangladeshi creatives and show them it is possible to break through the glass ceilings we sometimes find ourselves under.

Photo Credit: Uswa Ahmed