Roaming Reporter: The Struggle to Save The Harringay Warehouse District, and Beyond

By Sam Lailey, Senior Staff-Writer, MA Anthropology of Global Futures and Sustainability

Pull quote: “And gentrification appears to be picking up pace. A report released by the Trust for London in 2025 has highlighted 53 neighbourhoods in the capital which, between 2012 and 2020, have seen a significant drop in low-income and Black residents, as well as families with children”

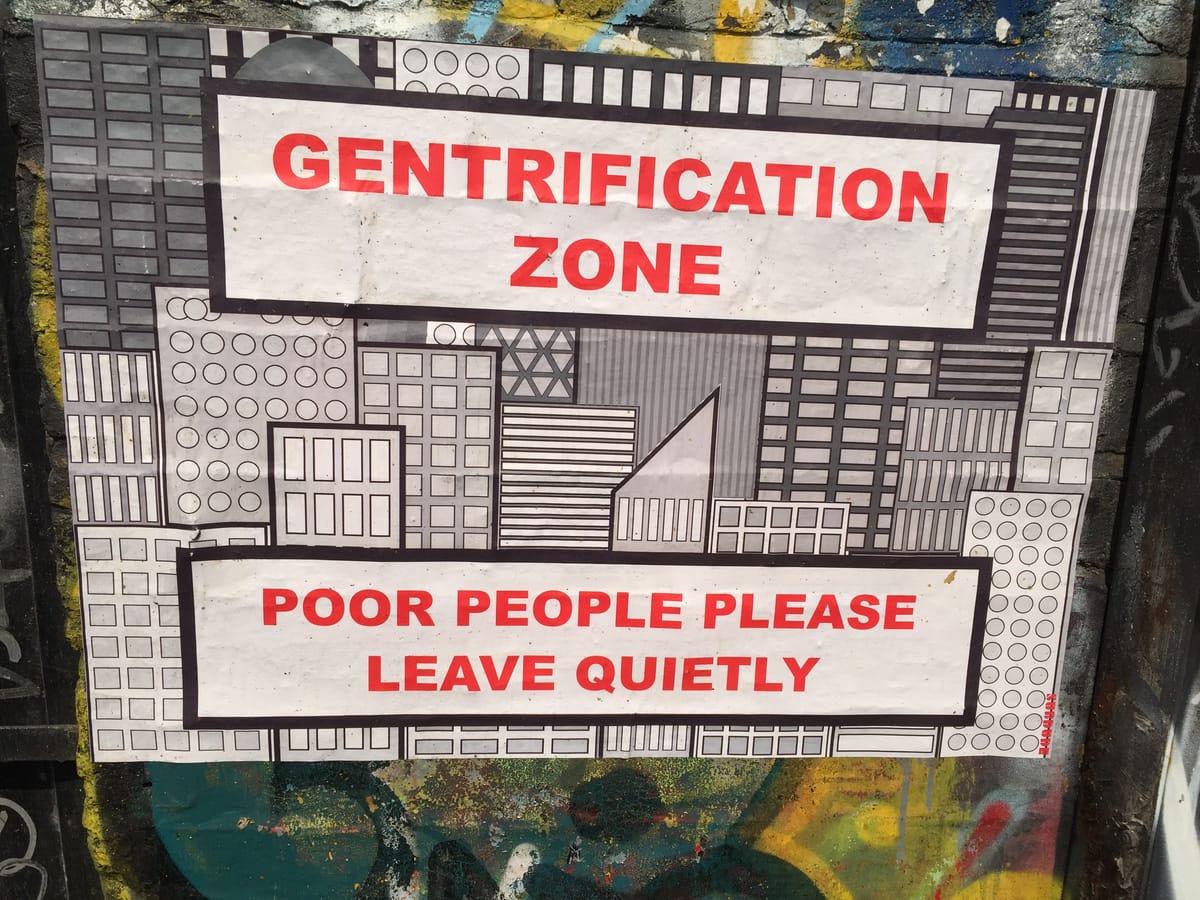

For those living in and around London, gentrification has become a familiar, almost daily part of our vocabulary. As this familiarity suggests, it is a process that many of us are intimately (and at times non-innocently) entangled with, often in complicated ways. The term captures everything from the seemingly never-ending expansion of high-street chains to the slow displacement of communities who get ‘priced-out’ of the neighbourhoods they once called home. This often happens through urban redevelopment projects, which are coated in a language of progress and renewal that attempts to mask their fundamentally exclusionary nature. And gentrification appears to be picking up pace. A report released by the Trust for London in 2025 has highlighted 53 neighbourhoods in the capital which, between 2012 and 2020, have seen a significant drop in low-income and Black residents, as well as families with children.

This all makes for gloomy reading. To my mind gentrification seems to have now acquired an air of almost mystical inevitability, portrayed as an unstoppable forward march towards an exclusionary dystopia for the better-off and well-to-do. I believe that debunking such a deterministic perspective requires shining a light on cases of resistance – places where hopeful sparks fly. Perhaps a nose-dive into one such community can offer a tentative starting point both for grappling with the embodied impacts of gentrification and envisioning ways it can be avoided.

I first heard about the Harringay* Warehouse District from my friend, who I will call Mimm (he has asked not to use his real name for fear of landlord reprisals). Mimm is a young artist-cum-activist who I have gotten to know whilst volunteering at a community garden in Finsbury Park. A while ago, he mentioned in passing that he had been embroiled in a campaign to prevent his community in Harringay from being gutted and redeveloped. Several months passed until I heard of this campaign again. In late 2025, Mimm arrived at the community garden with fantastic news. He told us how finally, after years of persistence, the planning application that had threatened the very existence of his community had been ‘formally disposed of.’ In a city where gentrification has become so ordinary, this seemed like a resounding – and rare - victory. Curious, I began to ask more and more questions. When I explained that I was interested in writing about gentrification, Mimm very kindly offered to take me on a tour of his neighbourhood. And so, one blustery Wednesday evening, I made my way down to the Harringay Warehouse District.

Mimm lives in a part of the district called Omega Works, which is the site of a former piano factory. From the outside, the warehouses appear unassuming – raw and rugged. However, as I stepped into the unit where Mimm lives, a very different picture emerged. A homely warmth radiated from the interior which had been organically crafted by its past and present dwellers. It was an ongoing process of additive design and redesign. Soft lighting illuminated the large room, while plants and trinkets gave it life. The inside space was also multidimensional. Given that most of the seven or eight residents who live there come from creative backgrounds, it fulfills the entangled needs of craftsmanship and livelihood. While I was there, one of Mimm’s cohabitants, a carpenter, provided a visual example of this as he sawed away at his latest project.

It is this creative vitality that developers were hoping to piggy back off when in 2021 they submitted plans to convert the Omega Works warehouses into multi-story flats and ‘warehouse inspired living’. Essentially, their proposal sought to repurpose the warehouses for a wealthier clientele.

In Mimm’s unit, we also met up with Erkin Kurtoglu, a PhD student from Oxford Brookes University who is currently studying how gentrification is affecting the warehouse community. Mimm was keen for me to listen to his insights on how gentrification works and what can be done to resist it. Erkin had been living for the last two months in a warehouse estate down the road called Arena Design Centre, to which we headed next. As we walked, both Mimm and Erkin explained how community opposition had quickly grown in response to the development proposals. Seeking to channel their angst, local residents formed ‘Save the Warehouses’, which Mimm had been part of. The dispute became high-profile; in 2023, a flurry of articles were released in the BBC, The Guardian and Vice, voicing residents’ concerns. Reflecting on the campaign, Mimm recounted how it took years of protracted struggle to finally see off the development applications.

The key to its success had apparently been the campaign’s ability to engage with the knitty-gritty of council policy. Molecular attention to legal frameworks and terminology allowed them to halt any advancements made in the planning applications. This, combined with heaps of perseverance, and the construction of solidarity networks with people both inside and outside the Omega Works community, allowed the group to successfully lobby Haringey Council to refuse the development plans. For the time being at least, the future of those currently living in the warehouse district finally seems more secure. This is no small feat for a campaign that, according to Mimm, was initially told ‘it didn’t have a hope in hell.’

Yet this victory also came with repercussions. Mimm in particular suffered mentally and emotionally from the years of uncertainty that put an unanswered question mark on his community’s future existence. In fact, he had first turned to gardening seeking an escape from the strain the development plans imposed on him. In Mimm, I saw gentrification transform from an abstract concept to an embodied reality.

My tour ended at New River Studios, the local bar and community hub. Over a pint, I asked Mimm and Erkin what community meant for them. Mimm emphasized the intrinsic importance of community for us all. For him, the interdependent lifestyles that the warehouses facilitate are both beautiful and a necessary remedy against the increasing atomisation and individualisation of wider society at large. Yet, he simultaneously stressed that warehouse living has its problems, and isn’t a utopia by any stretch of the imagination. For example, despite recent attempts to improve diversity, the warehouse communities tend to be predominantly White. Erkin also chimed in, elaborating on the importance of aligning interests between art-based and non-art-based residents across Haringey. This made me reflect on how the struggle to save the warehouses interconnects with other community struggles against gentrification.

While the unique character of Omega Works, combined with its creative vibrancy, allowed its residents to build enough traction to ward off developers this time round, I was left wondering: what becomes of those communities that can’t wield the same level of cultural clout? Indeed, both Mimm and Erkin stressed how residents living in the eastern part of the borough, historically the most deprived and marginalised area of Haringey, are now most vulnerable to gentrification. As Haringey prepares itself to take on the mantle of London Borough of Culture in 2027, there is a question mark over who the potential upswing cultural capital will serve. Existing communities? Or venture capitalists? And what should the role of creatives and artists be in mediating this process? Well aware of the dangers that this spotlight could bring, Erkin warned against ‘artwashing’: a process in which developers exploit the cultural allure created by an area’s artistic community. This pushes up rents, driving out existing residents. Of course, price hikes eventually drive the artists themselves out too. As the pair reminded me, if you want to see how this culminates, go no further than Hackney Wick.

The success of the Save the Warehouses campaign, against the grain of accelerating gentrification throughout London, should inspire us all. But however you want to measure success, this is not its endpoint. Perhaps the hopeful sparks generated in the Warehouse District can illuminate future imaginings of a London in which networks of solidarity fan out across and between communities. A London in which developers are forced to include existing residents in their utopic designs. And a London in which accountability lies at the heart of urban transformation. Indeed, the struggle to save the Harringay Warehouse District has created echo waves of possibility. The challenge now is surely to make those echoes reverberate far beyond the district’s borders.

* Not to be confused with the Borough of Haringey, in which it is located.