Russian Doping: The Saga Continues

By Fakhriya M. Suleiman, MA Global Media and Postnational Communications

The Russian doping saga was set in motion by the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympic Games. The Games saw the host nation initially achieve 33 medals – 13 were later expunged amid the federation’s doping scandal. The following year, however, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) declared the Russian Anti-Doping Agency (RUSADA) ‘non-compliant’.

WADA had launched an independent commission to investigate claims from a documentary made by German broadcasters ARD – ‘ The Secrets of Doping: How Russia makes its Winners’. The documentary implicated the Kremlin, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), now known as World Athletics (WA) as well as Russian athletes, coaches and doctors.

ARD’s documentary alleged RUSADA and a band of Russian coaches devised a ‘selective testing routine’ to ‘protect doped Russian athletes’. This clandestine partnership meant coaches would be tipped off by RUSADA officials of ‘surprise doping control tests’ – giving coaches ample time to ‘cover up’ test samples.

ARD’s accusations were confirmed in 2016 by former director of Russia’s anti-doping laboratory, Grigory Rodchenkov. In an article by the New York Times, Rodchenkov, who became a whistleblower, explained how members of the intelligence service were able to override the security at anti-doping centres and tamper with urine samples.

Although ARD, WADA and Rodchenkov had brought to the forefront the endemic nature of doping in the Kremlin, 2016 saw the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decide against the imposition of a blanket ban on Russian for the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Despite Rodchenkov exposing the fact that dozens of Russian athletes qualified for the 2014 Sochi Games under the Kremlin’s state-run ‘doping programme’, 271 athletes took part in the 2016 Games under the flag of Russia.

2018 saw the IOC change its stance when it banned Russia from competing at the PyeongChang Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games. This decision followed WADA chief Olivier Niggli’s findings that Russia was not doing enough to tackle its systemic doping problem. Yet, 169 ‘clean and vetted’ athletes were permitted to take part under ‘Team Olympic Athletes from Russia’.

To add to their sporting woes, 2019 saw WADA pass a four-year ban from all major sporting events on Russia. Russia was found to have tampered with laboratory data in January 2019.

WADA’s ban meant Russia would be excluded from the upcoming 2021 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics, the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics and the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.

Former Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev denounced WADA’s decision as a symptom of ‘chronic anti-Russian hysteria’ and cited the ban as unfair to his nation’s athletes who had ‘already been punished in one way or another’. Conversely, others have cited the international sporting community as not being tough enough on Russia for its string of doping misdemeanours – citing the likes of the IOC as being ‘too soft’.

The saga, now in its sixth year, sees Russia still vying for a spot on the international sporting stage. The summer of this year seemingly saw Russia turn a new leaf. In August, the Russian athletics federation (RUSAF) announced it had paid a £5m fine ($6.31m) for doping offences. WA had stated no Russian athlete, clean or otherwise, would be able to compete internationally if the fine was not paid.

Speaking in 2017, Beckie Scott, chair of WADA’s Athlete Committee, during a BBC interview said fining in Russia’s case ‘was not substantial enough for athletes’. Prior to being chair of the Athlete Committee, Scott was chair for WADA’s Compliance Review Committee (CRC), but stepped down from her post after WADA reinstantated Russia in 2016. For Scott, a ‘country involved in state-sponsored doping should not have the right to wave their flag at Olympic games’.

Jonathan Taylor, also a former chair of WADA’s CRC, in 2019 cautioned against an outright ban on Russia, citing that ‘it would be unfair on younger, innocent Russian athletes’. But, for Lord Sebastian Coe, WA President, this was a step in the right direction. Coe, himself an Olympic medallist, commented that this ‘breakthrough’ showed Russia had finally ‘accepted the severity of the situation’. However, according to Travis Tygart, head of America’s Anti-Doping Agency, ‘Russia hasn’t changed one bit.’

Following an investigation by British and American intelligence agencies, in October it emerged that Russia had launched cyber-attacks to disrupt the 2018 Winter Olympic Games. Further findings from the UK and US’ investigation indicate that operatives from the federation’s military intelligence branch were beginning attempts to target Tokyo’s upcoming Olympic Games, too.

Russia blames the 2018 Winter Olympic cyber-attack on North Korea and spokesman Dmitry Peskov charged the international sporting community with being ‘Russiaphobic’, asserting the federation ‘has never carried out any hacking activities against the Olympics’.

In light of this revelation, Japan’s chief cabinet secretary, Katsunobu Kato, said ‘mounted efforts’ would be put in place to protect the Games. Reuters reported that Kato also told a press conference that Japan was working with British and American authorities to ‘[gather and analyze] information, but gave no further details’.

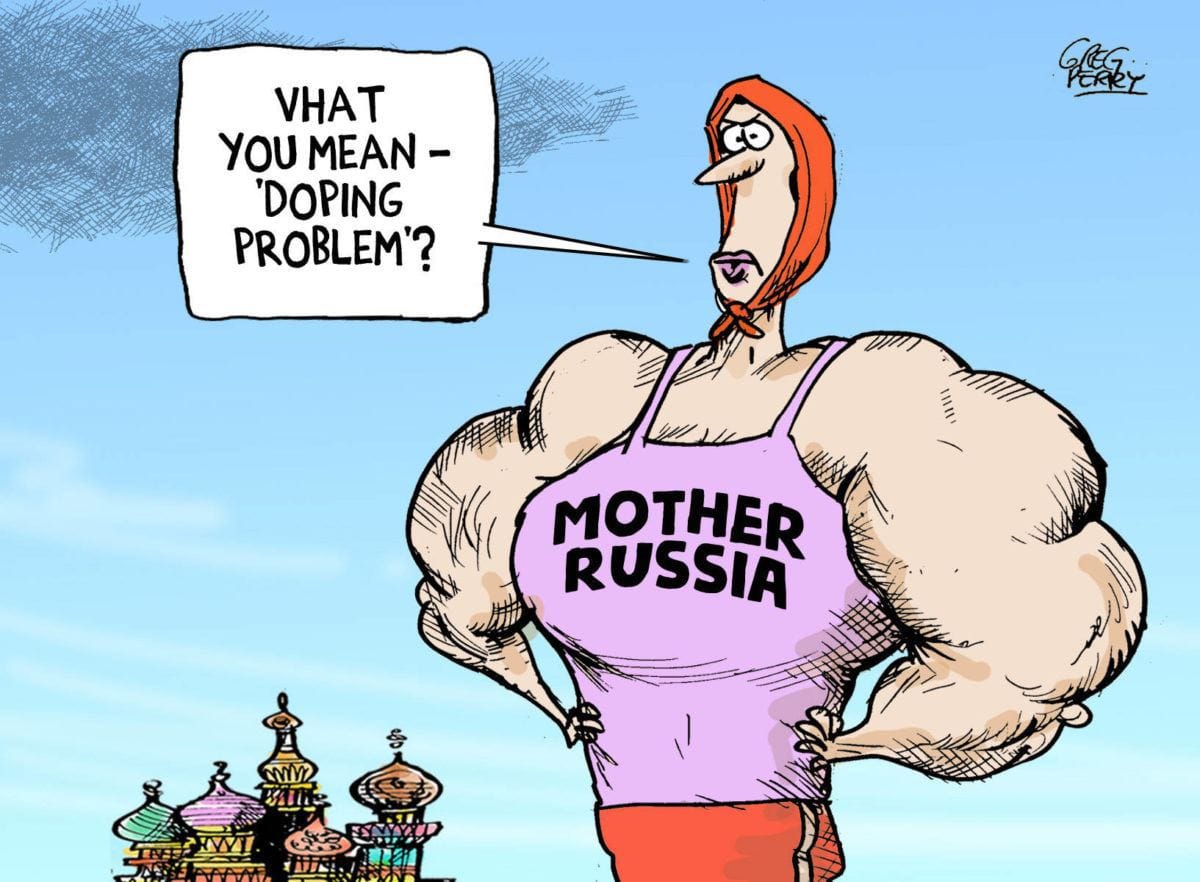

Photo Caption: A cartoon depicting the attitudes towards Russia’s doping problem (Credit: Perry GREG PERRY / PERRYINK).