The ‘Jewish Problem’: How Europe’s Anti-Semitism Created Israel

Nur Al-Hayah Leadbetter, BA International Relations

The term ‘Jewish Problem’ is one of history's most charged expressions which has been previously used to convey Europe's long, troubled relationship with its Jewish populations. While the language is grounded in prejudice and exclusion, it remains crucial to understanding how, after the Holocaust, European leaders reframed the ‘Jewish problem’ under the guise of finding a ‘solution.’ But this consisted of expelling Jewish populations elsewhere, rather than facing their own history of anti-Semitism.

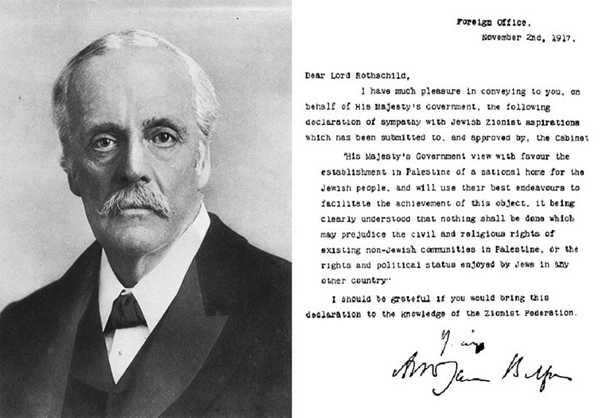

Israel was founded in 1948, based on the 1917 Balfour Declaration, promising a Jewish ‘national home’ in Palestine. Many in Europe saw the establishment of Jewish Land as an act of redemption, as a ‘safe haven’ for Jews, and as a declaration that these atrocities would never happen again. The founding of Israel became a moral narrative of repair, evidence allowing Europe to absolve itself of any guilt.

Yet this apparent act of conscience carried another dimension. By supporting the establishment of a Jewish state not on European land, European leaders' support for Israel appears to be performative. Instead of dismantling the systems of prejudice that had fuelled centuries of violence, they shifted their responsibility elsewhere. In this sense, the new state allowed Europe to express contrition without addressing the roots of the discrimination. The new state represented both a response to anti-Semitism and an escape from it.

This is where the paradox lies- the establishment of a Jewish homeland was intended as protection, yet it unfolded within a familiar colonial framework. The land that was given to Israel was not uninhabited. Palestinians who had lived there for generations suddenly found themselves subject to mass displacement. Policies of settlement and exclusion accompanied the moral language of redemption and refuge. One person's safety became another's dispossession.

This arrangement allowed Europe the moral convenience of supporting the establishment of Israel as a way for its post-war governments to recast themselves as defenders of human rights, but without the need to confront their complicated histories of exclusion and complicity. Moving from persecutor to patron was not merely political; it was psychological. The West could now tell itself that it had evolved, transforming guilt into virtue, all with little dismantling of the very structures that produced the violence in the first place.

The establishment of Israel cannot be read only as a moment of Jewish self-determination but also as a mirror reflecting Europe's ongoing unease with its past. The ‘solution’ to the so-called ‘Jewish Problem’ relocated Anti-Semitism. The language of humanitarianism masked a more profound continuity of prejudice and displacement, refigured in a new context. The land's richness rather than being recognized, was overwritten by a European vision that sought to solve a moral crisis at home by reshaping a region abroad.

In this sense, what Europe offered was not a sanctuary crafted with attention to the realities of those living there but instead a political arrangement built upon the erasure of one population's presence in order to compensate for its violence against another. This all reflects the European belief that they can redraw borders, repurpose land and reposition populations according to their own strategic or moral imperatives.

To sum up, Europe's moral crisis was externalized onto a terrain that already had a story, a people and a future of its own. Therein lies a disturbing and enduring moral paradox: a humanitarian gesture born in guilt, performed at a distance, is entangled in the very logic it sought to escape.