Windfall of £5m awarded to SOAS to improve teaching languages of the Global South

By Ludovica Longo, BA Politics and Geography

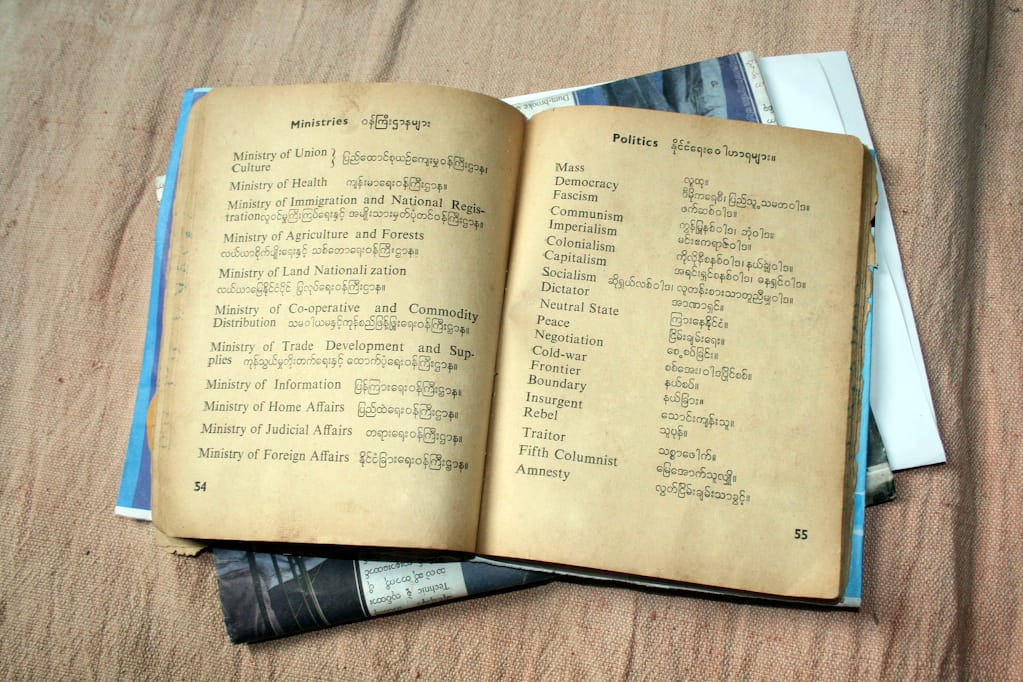

A £5m grant has been awarded to SOAS by the Higher Education Funding Council for England to improve and preserve engagement with the Global South through language. The money, from HEFCE’s Catalyst fund, will be invested in a project to safeguard UK provision in strategically important and vulnerable languages (SIL) of Africa, Asia and the Middle East such as Hausa, Somali, Swahili, Zulu, Urdu, Burmese, Khmer, Thai and Tibetan. As the only higher-level institution in the UK teaching 22 African and Asian languages, 13 of which are exclusively taught in our university, SOAS’ key role in this area might prove even more relevant at a time in which the UK is shifting its focus from Europe and positioning itself outwardly to the non-European world.

Professor Lutz Marten, Dean of the Faculty of Languages and Cultures, who led the bid, said: “Knowledge and understanding of these languages and associated cultures is becoming increasingly important for the UK and its wider international interests – for critical understanding of geopolitics and diplomacy, and of global cultural dynamics, for international development, international business and trade, and social cohesion within the UK. The project aims to maintain and strengthen provision in these languages in the future.”

In order to protect the country’s strategic position as a global leader in free trade and international relations, British language institutions have been called upon to resolve the language skills deficit, which is estimated to cost up to 3.5 % of national GDP. The education system must take on a fundamental role preparing a generation of linguistically proficient graduates to replace EU officials’ functions of negotiating trade deals with the Global South. To further complicate the picture, SOAS and other language centers in the country will have to overcome a predicted teacher shortage as a direct effect of Brexit.

The £5m may be of value to SOAS’s plans to renovate and refurbish the infrastructure surrounding language teaching in the existing SOAS estate. Alongside physical improvements, SOAS plans to start a fundraising campaign to ultimately raise £10m to underpin staff costs and fund both the teaching of current languages and language-related scholarships.

An ambitious reform of the curriculum has also been tabled that would allow every student enrolled at SOAS to learn a language as part of their degree. The latter would match our institution’s main historical reputation of dominant institution in terms of cultural and linguistic expertise of the Global South. As well as being of strategic importance many of the languages on the list have historically been ‘vulnerable’ and still are subject to pressure and competition with European languages.

Professor Marten added that the creation of a hierarchy of languages traces back to a colonial narrative in which the language of the colonizers was imposed at the expenses of original languages local dialects. He said “a paradigm of linguistic equality” is now the ultimate goal, adding: “To study Burmese or Thai is exactly the same as studying English and French in terms of academic and intellectual value.”

Despite the fact that none of the 22 languages in the list are in danger of extinction, the majority of the latter group are spoken in the areas covered. Knowledge of a Catalyst language is therefore needed as research tool in order to work with local communities for the common goal of protecting endangered languages.