Few Answers Materialise in Controversy Around SOAS’ Rare Buddha Statue

Caren Holmes, MA Postcolonial Studies

In March 2018, SOAS accepted a controversial gift from American alumni, Mary and Paul Slawson. The gift, a 13th-century Thai sculpture, housed within the Brunei Gallery, is estimated to be worth more than €60,000 but lacks documentation of its transactional history.

Dr Angela Chiu, who has a PhD in Thai Art History, discovered the sculpture in the Brunei Lobby. Immediately recognizing its significance as a 700-year-old Thai sculpture, she led efforts to retrieve answers from administrators surrounding the acquisition of the piece, publishing her findings on her blog, SOASWatch.org.

Given the severity of looting throughout the colonial era, international governing bodies have endorsed policies to redress centuries of pillaging, facilitating efforts between international governments to return stolen cultural artefacts. Under international ethics requirements, art museums agree to pay particularly close attention to the history of their artefacts in an effort to prevent the continued circulation of stolen goods. The UK Museums Association says within its guidance on ethical acquisition, that museums should “reject any item that lacks a secure ownership history unless there is reliable documentation to show it was exported from its country of origin before 1970” (Clause 2.8).

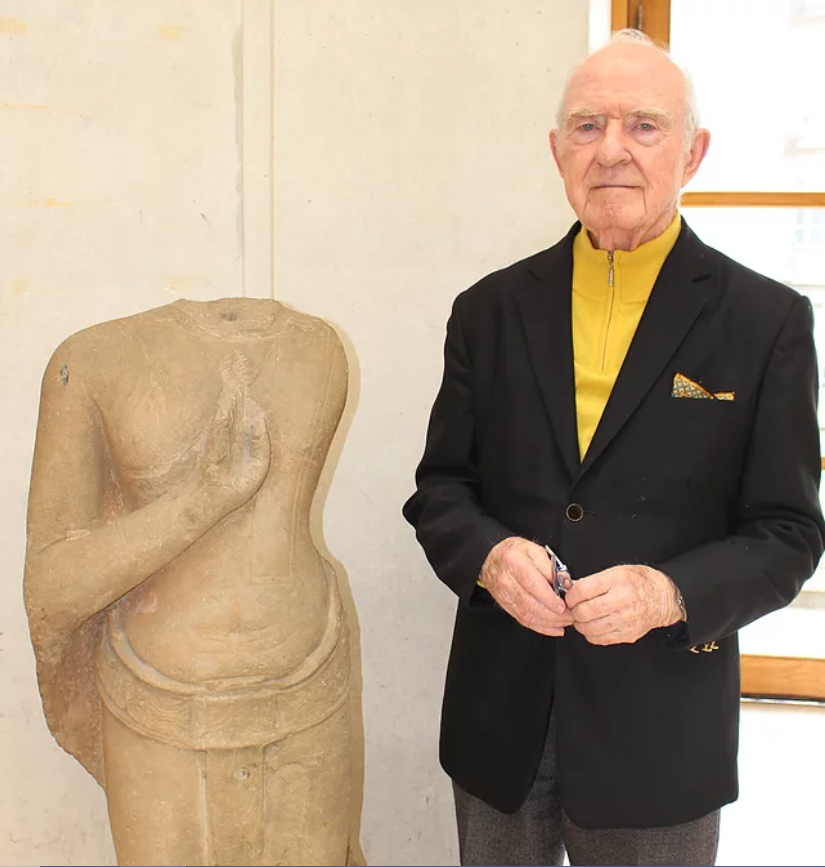

Paul Slawson, the alumni who provided the donation, explains in emails with the university, that he bought the Thai Lopburi Buddha torso in the UK during the 1980s at the Ormond Gallery on Portobello Road. Following an FOI request, released email exchanges between Slawson and SOAS showed that Slawson had no records of the torso arriving in the UK, but he was told by the art dealership where he purchased the piece that it had been acquired in the US in what is described in emails as a “California Hippy Shop.” There is though, no evidence of the sculpture’s whereabouts which would satisfy the 1970 standard outlined above.

In its guidelines for museums, libraries and archives, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport calls on institutions to undertake due diligence in checking on the provenance of their artefacts. “Museums must be able to establish where an item came from, and when and how it left its country of origin and any intermediate country.” The policy explains that museums have to establish one of three things: have evidence that the piece was in the UK prior to 1970; have evidence that the piece was out of its country of origin prior to 1970 and have evidence of its importation into the UK; or have evidence that it was still in its country of origin after 1970, and have evidence documenting its legal exportation to the UK. The Buddha Torso donated to SOAS doesn’t meet any of these three requirements.

In a public statement on the acquisition of the statue, a SOAS spokesperson explained that the university followed its own internal policies of due diligence “carried out by SOAS in accordance with SOAS’ Collections Management Policy and SOAS’ Due Diligence Procedure for the acceptance of Philanthropic Gifts.” However, the relationship these policies have to national and international standards of cultural artefact acquisition is unclear. A SOAS spokesperson explained that the internal policies in question are due to go under review this year.

Dr Chiu argues that the university’s efforts to meet standards of due diligence under SOAS policy are insufficient as the policies are not designed to handle the complexities of acquiring cultural artefacts. Administrators have argued that their efforts to track the item on two looted artefact databases, clear the item of suspicion, but Chiu explains that the databases they used “have little or no information regarding Thai artefacts,” suggesting that such searches would provide little assurance that the sculpture wasn’t looted.

In June, Chiu contacted Thai embassy authorities about the artefact. They confirmed the Thai origins of the piece and agreed to open conversations with the university surrounding its history. According to a SOAS spokesperson, the Thai ambassador has been shown the sculpture but there has been no further discussion about its history and provenance.

“Dr Chiu argues that the university’s efforts to meet standards of due diligence under SOAS policy are insufficient as the policies are not designed to handle the complexities of acquiring cultural artefacts.”

The “Decolonising SOAS Vision”, approved by the academic board of the university in 2017, dictates a requirement to develop “a stronger commitment to actively make redress for [impacts of colonialism] through ongoing collective dialogue within the university and through our public obligations.” When asked how the acquisition of this sculpture aligned with the goals of decolonizing the university, a SOAS spokesman explained that the artefact “provides a platform for just these kinds of discussions and for them to be evaluated.”

In promotional material produced by the university, advertising Slawson’s donation to the school, Slawson explains, “One should never aspire to truly own such an ancient statue as this… just a shared living experience for a while and then returned to be shared with others.” But perhaps, like artefacts housed within former colonial empires, this 13th-century sculpture may actually belong somewhere other than SOAS. Without following internationally recognized standards of ethical acquisition, the SOAS community cannot know this for certain.